Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie leave the Sarajevo Town Hall on 28 June 1914, five minutes before the assassination.

The Good Soldier Švejk is a novel with an unusually rich array of characters. In addition to the many who directly form part of the plot, a large number of fictional and real people (and animals) are mentioned; either through the narrative, Švejk's anecdotes, or indirectly through words and expressions.

This web page contains short write-ups on the people that the novel refers to; from Napoléon in the introduction to Hauptmann Ságner in the last few lines of the unfinished Part Four. The list is sorted in the order of which the names first appear. The chapter headlines are from Zenny Sadlon's recent translation (1999-2024) and will in most cases differ from Cecil Parrott's version from 1973.

The quotes in Czech are copied from the on-line version of The Good Soldier Švejk: provided by Jaroslav Šerák and contain links to the relevant chapter. The toolbar has links for direct access to Wikipedia, Google maps, Google search, svejkmuseum.cz and the novel on-line.

The names are coloured according to their role in the novel, illustrated by the following examples:

- Dr. Grünstein as a fictional character who is directly involved in the plot.

- Fähnrich Dauerling as a fictional character who is not part of the plot.

- Heinrich Heine as a historical person.

Note that a number of seemingly fictional characters are inspired by living persons. Examples are Oberleutnant Lukáš, Major Wenzl and many others. This are still listed as fictional because they are literary creations that are only partly inspired by their like-sounding "models".

Military ranks and some other titles related to Austrian officialdom are given in German, and in line with the terms used at the time (explanations in English are provided as tooltips). This means that Captain Ságner is still referred to as Hauptmann although the term is now obsolete, having been replaced by Kapitän. Civilian titles denoting profession etc. are translated into English. This also goes for ranks in the nobility, at least where a direct translation exists.

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (588)

Show all

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (588)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30)

1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30) 14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46) 5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (45)

5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (45) III. The famous thrashing

III. The famous thrashing  1. Across Magyaria (52)

1. Across Magyaria (52) 2. In Budapest (32)

2. In Budapest (32) 3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31)

3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31) 4. Forward March! (32)

4. Forward March! (32) IV. The famous thrashing continued

IV. The famous thrashing continued  1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35)

1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35) 3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

|

III. The famous thrashing |

| |

2. In Budapest | |||

| Špatina |  | |||

| |||||

Špatina from Zhoř is about to feature in a story when Oberleutnant Lukáš resolutely interrupts the diligent narrator Švejk.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] „Poslušně hlásím, pane obrlajtnant“ řekl s obvyklou ohebností Švejk, „věc, o kterou jde, je nesmírně důležitou. Prosil bych, pane obrlajtnant, abychom mohli tu celou záležitost vyřídit někde vedle, jako říkal jeden můj kamarád, Špatina ze Zhoře, když dělal svědka na svatbě a chtělo se mu najednou v kostele...“

Literature

- Jak se stal Milan Špatina atheistou, Jaroslav Hašek,7.5.1914

| Sculptor Scholz, Heinrich Karl |  | |||

| *Lub u Frýdlantu (Mildenau) 16.10.1880 - †Wien 12.6.1937 | |||||

| |||||

Scholz was, in the authors words, the sergeant, one-year volunteer, shirker and sculptor behind the war grave memorial in Sedlisko in western Galicia. The soldiers of Švejk's march company were instead of the promised cheese given a postcard from this cemetry, depicting som unfortunate men from k.k. Landwehr.

Background

Scholz was a noted academic sculptor from northern Bohemia who during World War I was responsible for more than 50 war cemeteries and memorials in the area of Tarnów-Gorlice, including those in Siedliska. His statue, "Nackter Krieger" (Naked Warrior) is amongst those that still exists.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Místo patnácti dekagramů ementálského sýra měl každý v ruce západohaličský hřbitov vojínů v Sedlisku s pomníkem nešťastných landveráků, zhotovených ulejvákem-sochařem, jednoročním dobrovolníkem šikovatelem Scholzem.

| Merchant Hořejší |  | |||

| |||||

Hořejší is mentioned in Švejk's tale related to Italy's entering the war in 1915 against its formal allies, here illustrated by three merchants in Táborská ulice.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] „V Táborskej ulici v Praze byl taky takovej případ,“ začal Švejk. „Tam byl ňákej kupec Hořejší, kus vod něho dál naproti měl svůj krám kupec Pošmourný a mezi nima voběma byl hokynář Havlasa. Tak ten kupec Hořejší jednou dostal takovej nápad, aby se jako spojil s tím hokynářem Havlasou proti kupci Pošmournýmu, a začal s ním vyjednávat, že by mohli ty dva krámy spojit pod jednou firmou: ,Hořejší a Havlasa’.

| Merchant Pošmourný |  | |||

| |||||

Pošmourný is mentioned in Švejk's tale related to Italy's changing of allegiance in 1915, here illustrated by three merchants in Táborská ulice.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] „V Táborskej ulici v Praze byl taky takovej případ,“ začal Švejk. „Tam byl ňákej kupec Hořejší, kus vod něho dál naproti měl svůj krám kupec Pošmourný a mezi nima voběma byl hokynář Havlasa. Tak ten kupec Hořejší jednou dostal takovej nápad, aby se jako spojil s tím hokynářem Havlasou proti kupci Pošmournýmu, a začal s ním vyjednávat, že by mohli ty dva krámy spojit pod jednou firmou: ,Hořejší a Havlasa’.

| Grocer Havlasa |  | |||

| |||||

Havlasa is mentioned in Švejk's tale related to Italy changing allegiance in 1915, here illustrated by three merchants in Táborská ulice.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] „V Táborskej ulici v Praze byl taky takovej případ,“ začal Švejk. „Tam byl ňákej kupec Hořejší, kus vod něho dál naproti měl svůj krám kupec Pošmourný a mezi nima voběma byl hokynář Havlasa. Tak ten kupec Hořejší jednou dostal takovej nápad, aby se jako spojil s tím hokynářem Havlasou proti kupci Pošmournýmu, a začal s ním vyjednávat, že by mohli ty dva krámy spojit pod jednou firmou: ,Hořejší a Havlasa’.

| Chovanec |  | |||

| |||||

Chovanec was a grandfather from Motol who spanked kids on behalf of the parents for a flat fee. This is mentioned by Švejk to emphasize that it now is more important than ever to use ammunition sparingly as there was one more enemy (Italy).

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] „Když už tedy zas máme novou vojnu,“ pokračoval Švejk, „když máme vo jednoho nepřítele víc, když máme zas novej front, tak se bude muset šetřit s municí. ,Čím víc je v rodině dětí, tím více se spotřebuje rákosek,’ říkával dědeček Chovanec v Motole, kerej vyplácel rodičům v sousedství děti za paušál.“

| Skorkovský |  | |||

| |||||

Jiří Skorkovský, redaktor "Českoho slova" ...

© Národní archiv - Archiv České strany národně sociální

Skorkovský is a lower ranking bank clerk who forms part of Švejk's long urine analysis story. He decides to take revenge on the annoying "urine analyser" by sending him on duty to the quarrelsome house porter domovník Málek. He worked in some house in Vinohrady where Švejk lived at the time.

Background

This anecdote has much in common with the story Analysa moče (Analysis of Urine) that Hašek had printed in the satirical magazine Kopřivy in 1912. Here the author himself has the role of Škorkovský and the ill-tempered custodian is called Jan Vaňous and lives in Čelakovského 24. This was actually the home address of Hašek from 1901 to 1906!

In the story the urine obsessed man was named as a certain Mašek who together with Hašek was an apprentice at drogerie Průša. The two fell out and Hašek exacted revenge by sending him a letter, informing that the custodian needed his urine analysed. The result is much the same as we know it from The Good Soldier Švejk...

Borrowed name?

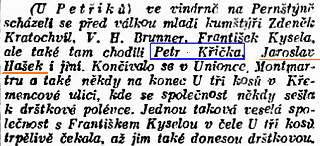

It is quite possible that Jaroslav Hašek borrowed the name of his bank clerk from Jiří Skorkovský, a politician from Česká strana národně sociální who for a period was editor at the party newspaper České slovo. This was a publication that Hašek also wrote for and he was briefly employed by twice.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Všichni, co chodili do výčepu, i hostinský a hostinská, dali si moč analysovat, jenom ten úředníček se ještě držel, ačkoliv ten pán za ním lez pořád do pissoiru, když šel ven, a vždycky mu starostlivě říkal: ,Já nevím, pane Skorkovský, mně se ta vaše moč nějak nelíbí, vymočte se do lahvičky, dřív než bude pozdě!’ Konečně ho přemluvil.

Literature

- Analysa moče, Jaroslav Hašek,4.7.1912

- Hrst nezabudek, sázených na hrob strany národně sociální, Jaroslav Hašek,26.3.1914

| Domovník Málek |  | |||

| |||||

,18.5.1924

Málek is part of Švejk's long story about urine analysis, to illustrate that the victim of revenge may not be the person it's directed against. In this story it is revealed that Švejk long ago lived in Vinohrady, and that Málek was the ill-tempered custodian in the building where Švejk lived. The main person in the anecdote is not mentioned by name, but he ran a firm that carried out analysis of urine.

He was very persistent and tried to persuade everyone he met to have heir urine analysed. He rubbed the bank official Skorkovský up the wrong way with his urine analysis but the latter took revenge by telling the urine analyser that Málek needed an analysis.

When the irritable porter was woken up for this purpose at 7 in the morning he was less than pleased, and dressed in his underpants he chased the urine man across half of Vinohrady. In the end Málek was arrested and sentenced for breach of public order, whereas the intended victim of the revenge act got away.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] A von tam šel. Domovník ještě spal, když ho ten pán vzbudil a povídal mu přátelsky: ,Moje úcta, pane Málek, dobré jitro přeji. Tady prosím lahvička, račte se vymočit a dostanu šest korun.’ Ale to bylo boží dopuštění potom, jak ten domovník vyskočil v kaťatech z postele, jak toho pána chyt za krk, jak s ním praštil vo almaru, až ho do ní zafasoval!

Literature

- Analysa moče, Jaroslav Hašek,4.7.1912

| Emperor Ferdinand I. |  | |||

| *19.4.1793 Wien - †29.6.1875 Praha | |||||

| |||||

Ferdinand I. is mentioned when Leutnant Dub gets introduced to the reader.

Background

Ferdinand I. was the predecessor of Emperor Franz Joseph I. on the Austrian throne, king of Hungary and the last crowned king of Bohemia. He was unofficially called Ferdinand der Gütige (Ferdinand the Good/Benign), however, after his abdication during the revolutions of 1848, this was often reversed to Gütinand der Fertige (Goodinand the Finished). He ruled from 1835 to 1848 and then lived on Hradčany from his abdication until his death.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] V nižších třídách strašil žáky císař Maxmilián, který vlezl na skálu a nemohl slézt dolů, Josef II. jako oráč a Ferdinand Dobrotivý.

| Emperor Joseph II. |  | |||

| *13.3.1741 Wien - †20.2.1790 Wien | |||||

| |||||

Joseph II. is mentioned when Leutnant Dub gets introduced to the reader.

Background

Joseph II. was Austrian emperor from 1780 to 1790, son of Empress Maria Theresa. He was known for a succession of political and educational reforms, and is considered and enlightened ruler for his time. Amongst the reforms were: relegious freedom (benefited the Jews), tax on the nobility, abolishment of serfdom, abolishment of capital punishment in civilian courts, compulsory education, dissolution of 700 monasteries, and many sosial reforms. He was forced to withdraw many of these before he died.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] V nižších třídách strašil žáky císař Maxmilián, který vlezl na skálu a nemohl slézt dolů, Josef II. jako oráč a Ferdinand Dobrotivý.

Also written:Josef II.czJoseph_II.de

| Weiner |  | |||

| |||||

, 25.12.1915

Weiner was an actress who Hauptmann Ságner had seen on stage in Bruck, and who now, according to Pester Lloyd, performed at Kis Színkör in Budapest.

Background

Weiner may have been Hansy Weiner who featured in Sport und Salon on 25 December 1915. She appeared at Volksoper in Vienna and was a talented singer. It has not been possible to identify the advert in Pester Lloyd which is mentioned in the novel.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Zklamal se však úplně, neboť hejtman Ságner, kterému přinesl batalionsordonanc Matušič ze stanice večerní vydání „Pester Lloydu“, řekl, dívaje se do novin: „Tak vida, ta Weinerová, kterou jsme viděli v Brucku vystupovat pohostinsky, hrála zde včera na scéně Malého divadla.“

| Archbishop Géza ze Szatmár-Budafalu |  | |||

| |||||

János Csernoch, archbishop of Esztergom from 1912 to 1927.

Arthur Winnington-Ingram

Géza ze Szatmár-Budafalu was according to the author archbishop of Budapest, the author of two prayers who contained the most terrible curses on the enemies.

Background

The archbishop is presented as a real person but nothing is known about him apart from what is evident from the text. Hans-Peter Laqueur points out that lists of bishops and archbishops in Hungary show no traces of any such person. Moreover the Archbishop-seat of Hungary was located in Esztergom, making it even more likely that this person is fictional. The combination Szatmár and Budafalu is also improbable: the first being a city and county name, the second a village. For the record: the archbishop of Esztergom who was also responsible for Budapest was from 1912 onwards János Csernoch (Slovak: Ján Černoch)[b].

A bishop's seat that actually existed was Szatmár-Neméti (now Satu Mare in Romania) so the author may have thrown about some names to create his literary archbishop.

The bishop of London

There were surely several examples of belligerent clerics, and on all sides in the conflict. Best known amongst these is probably the bishop of London, Arthur Winnington-Ingram (1858-1946). On 28 November 1915 he held an advent sermon where he allegedly wished death on the Germans, "the good as well as the bad, in order to save our civilisation"[1]. He used words that came close to those of poet Vierordt although less grotesque.

Whether Jaroslav Hašek was aware of those utterances is however unlikely. The sermon took place at a time when the author of The Good Soldier Švejk was already in Russian captivity. He may still have heard of it later, but it was only after the war that the content of the sermon became known to a wider public. More likely he was inspired by the utterances of some cleric closer to home or he may simply have invented the story.

1. This version has been refuted by Stuart Bell a.o. who states that the infamous quote comes from a heavily abridged version, published by The Secular Society in the thirties[a].

Tamás Herczeg

There has never been any archbishop called "Gézou ze Szatmár-Budafalu" (Szatmár-Budafalusi Géza in Hungarian) in Hungary. However, a compilation of speeches and prayers for war time existed in Hungarian language, whose editor was professor Dr. Lencz Géza at the Faculty of Theology of the University of Debrecen. The compilation was published in three parts in 1914 and 1915 and was popular among chaplains. An article in the 2nd part was written by József Fülöp and gives really examples on Herodes, as Hasek mentioned it. But as far as I know the articles of Dr. Lencz's books were not translated into other languages and not distributed among soldiers. For these purposes mostly Aladár Reviczky's (1874-1921, theologist) articles were used. They were published first in 1909, but a rewritten edition was published in 1914 and translated to German, Slovakian, Polish, Croatian, Italian and Romanian. I suppose that Hasek met both Lencz's book and Reviczky's bilingual prayers, but remembered only the name "Géza" and composed a fictional name and rank "budapeštským arcibiskupem Gézou ze Szatmár-Budafalu". I must note, that the speeches and prayers are not so vulgar as it is demonstrated by Hasek.

Winnington-Ingram

(probably from an abridged inter-war version). Everyone that loves freedom and honour … are banded in a great crusade – we cannot deny it – to kill Germans; to kill them, not for the sake of killing, but to save the world; to kill the good as well as the bad, to kill the young as well as the old, to kill those who have shown kindness to our wounded as well as those fiends who crucified the Canadian sergeant, who superintended the Armenian massacres, who sank the Lusitania, and who turned the machine-guns on the civilians of Aerschott and Louvain – and to kill them lest the civilisation of the world itself be killed.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Kromě toho přinesly ustarané, utahané dámy veliký balík vytištěných dvou modliteb sepsaných budapešťským arcibiskupem Gézou ze Szatmár-Budafalu. Byly německo-maďarské a obsahovaly nejstrašnější prokletí všech nepřátel. Psány byly tyto modlitbičky tak vášnivě, že tam jenom na konci scházelo řízné maďarské „Baszom a Krisztusmárját!“

Credit: Hans-Peter Laqueur, Tamás Herczeg

Also written:Géza of Szatmár-BudafaluenSzatmár-Budafalusi GézahuGéza av Szatmár-Budafaluno

Literature

- The Belligerent Bishop, ,2012

- What the Bishop said (or, the truth about the Bishop of London…), [a]

- János Csernoch, [b]

| a | What the Bishop said (or, the truth about the Bishop of London…) | ||

| b | János Csernoch |

| Šimek |  | |||

| |||||

Šimek was a soldier who was patted on the cheek by a lady from The Society for welcoming of Heroes. His comment was that the whores were very cheeky here.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Byl to nějaký Šimek z Budějovic, který neznaje ničeho o tom vznešeném poslání těch dam, prohodil k svým soudruhům po odchodu dám: „Jsou ale tady ty kurvy drzý. Kdyby aspoň taková vopice vypadala k světu, ale je to jako čáp, člověk nic jiného nevidí než ty haksny a vypadá to jako boží u.mučení, a ještě si taková stará rašple chce něco začínat s vojáky.“

| Rechnungsfeldwebel Bautanzel |  | |||

| |||||

Bautanzel is an accounting seargent by the march batallion, an expert in siphoning off food meant for the soldiers. He describes in detail how the theft occurs, illustrated by examples from march battalions he has been with earlier in the Carpathians. See also Major Sojka. He also complains about the increasingly poor provisions and remembers the halycon days at the beginning of the war. He also describes the superior provisions of the Prussians, who offered twice as much in compensation for requisitions.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Ve vagonu, kde byla kancelář a skladiště batalionu, účetní šikovatel pochodového praporu Bautanzel velmi blahosklonně rozdal dvěma písařům od batalionu po hrsti ústních pokroutek z těch krabiček, které se měly rozdat mezi batalion.

| Major Sojka |  | |||

| |||||

Sojka was a major who Rechnungsfeldwebel Bautanzel had served with on one of his two trips to the Carpathians with previous march battalions. Sojka enjoyed food, and had a tendency to loiter around the field kitchen at all times, particularly when shrapnel and bullets started flying.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Za tu celou dobu nic víc se mně nepodařilo ušetřit pro nás v kanceláři než jedno prasátko, které jsme si dali vyudit, a aby ten major Sojka na to nepřišel, tak jsme ho měli uschované hodinu cesty u artilerie, kde jsem měl jednoho známého feuerwerkra.

| Fähnrich Wolf |  | |||

| |||||

Wolf was a junior officer who had a whispering conversation with Oberleutnant Kolář about rumours that Oberst Schröder had sent illicit money to his bank in Vienna.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Nastal vzájemný šepot mezi fähnrichem Wolfem a nadporučíkem Kolářem, že plukovník Schröder za poslední tři neděle poslal na své konto do vídeňské banky 16.000 K.

| Oberleutnant Kolář |  | |||

| |||||

Kolář was a senior lieutenant who had a whispering conversation with Fähnrich Wolf about rumours that Oberst Schröder had sent illicit money to his bank in Vienna. Oberleutnant Kolář went on to explains in general terms how the fraud is carried out.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Nastal vzájemný šepot mezi fähnrichem Wolfem a nadporučíkem Kolářem, že plukovník Schröder za poslední tři neděle poslal na své konto do vídeňské banky 16.000 K.

| Oberst Wachtl |  | |||

| |||||

Wachtl was a colonel from Švejk's time doing national service who he mentions when answering the Polish latrine-obsessed general that a soldier can not only think about shitting, he must think about fighting as well.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] „Poslušně hlásím, pane generálmajor, na manévrech u Písku říkal nám pan plukovník Wachtl, když mužstvo v době rastu se rozlézalo po žitech, že voják nesmí pořád myslet jen na šajseraj, voják že má myslet na bojování. Ostatně, poslušně hlásím, co bychom tam na tý latrině dělali? Není z čeho tlačit. Podle maršrúty měli jsme už dostat na několika stanicích večeři, a nedostali jsme nic. S prázdným žaludkem na latrinu nelez!“

| Jesenská, Růžena |  | |||

| *17.6.1863 Smíchov - †14.7.1940 Praha | |||||

| |||||

, 25.4.1933

Růžena Jesenská is mentioned as Švejk is squatting on the latrine in Budapest and reads a torn-off sheet from a novel by Růžena Jesenská.

Background

Růžena Jesenská was a Czech author and poet, who published books on upbringing of children (amongst other themes). As and advocate of premarital sex she was heavily criticised in her time. She was the aunt of the much better known Milena Jesenská.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Na levém křídle seděl Švejk, který se sem připletl, a se zájmem si přečítal útržek papírku, vytrženého bůhví z jakého románu Růženy Jesenské:

..dejším pensionátě bohužel dámy em neurčité, skutečné snad více ré většinou v sebe uzavřeny ztrát h menu do svých komnat, aneb se svérázné zábavě. A utrousily-li t šel člověk jen a pouze stesk na ct se lepšila, neb nechtěla tak úspěšně covati, jak by samy si přály. nic nebylo pro mladého Křičku

Credit: Milan Hodík, Wikipedia

| Křička |  | |||

| |||||

Petr Křička

,17.11.1928

,16.8.1926

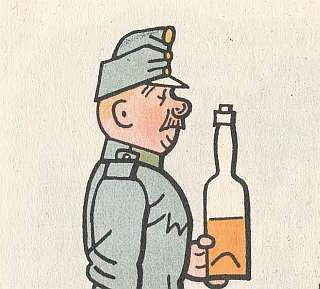

Křička is mentioned in the fragment of a novel by Růžena Jesenská which Švejk reads when he is squatting on the latrine in Budapest.

Background

The mentioned book fragment can not be traced in any literature by Růžena Jesenská. It is either taken from another writer or simply invented. In the latter case it may be that Hašek pokes fun at one or two of his contemporaries.

An obvious candidate amongst these is the poet and translator Petr Křička (1884-1949) who he knew from the wine bar U Petříku where they both visited. Břetislav Hůla mentions him as a person that could provide information about Jaroslav Hašek. Another possible source of inspiration: in a letter to his future wife Jarmila, dated 21 July 1908, the author mentions an architect Křička he had met in Kolín. This was Čeněk Křička (1858-1948) who was also a politician and for a while mayor of the city.

Another possible source of inspiration: in a letter to his future wife Jarmila, dated 21 July 1908, the author mentions an architect Křička who he had met in Kolín. The person in question was Čeněk Křička (1858-1948), a politician who later became mayor of the city.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2]

..dejším pensionátě bohužel dámy em neurčité, skutečné snad více ré většinou v sebe uzavřeny ztrát h menu do svých komnat, aneb se svérázné zábavě. A utrousily-li t šel člověk jen a pouze stesk na ct se lepšila, neb nechtěla tak úspěšně covati, jak by samy si přály. nic nebylo pro mladého Křičku.

Credit: Břetislav Hůla, Jiří Fiala, Sergey Soloukh, Václav Menger

Also written:KříčkaParrottKeitschkaReiner

| Korporal Málek |  | |||

| |||||

Málek was the first to assume the original shitting position after the latrine general in Budapest surprised the company with their trousers on their knees.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Generálmajor přívětivě se usmál a řekl: „Ruht, weiter machen!“ Desátník Málek dal první příklad svému švarmu, že musí opět do původní posice. Jen Švejk stál a salutoval dál, neboť z jedné strany blížil se k němu hrozivě poručík Dub a z druhé generálmajor s úsměvem.

| Leutnant Chudavý |  | |||

| |||||

Chudavý was a lieutenant at the Karlín barracks who Švejk reminisced about after receiving yet another tirade from Leutnant Dub.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Švejk odcházel konečně k svému vagonu a přitom si pomyslil: Jednou byl, když jsme ještě byli v Karlíně v kasárnách, lajtnant Chudavý a ten to říkal jinak, když se rozčilil: „Hoši, pamatujte si, když mne uvidíte, že jsem svině na vás a tou sviní že zůstanu, dokud vy budete u kumpanie.“

| Mr. István |  | |||

| |||||

István from Isatarcsa was victim of Švejk's alleged hen theft. The good soldier was led to the staion in Budapest by the miltary police after it was claimed that he stole the hen, and had hit István with it so he got a blue eye. Švejk denied this, they had only been argueing about the price. In the end he got away with paying ten guilders, five for the hen and five for the blue eye.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Veliteli 11. marškumpanie N pochodového praporu 91. pěšího pluku k dalšímu řízení.

Předvádí se pěšák Švejk Josef, dle udání ordonance téže marškumpanie N pochodového praporu 91. pěšího pluku, pro zločin loupeže, spáchaný na manželích Istvánových v Išatarča v rayoně velitelství nádraží.

| Mrs. István |  | |||

| |||||

István from Isatarcsa was together with her husband victim of Švejk's alleged hen theft. The good soldier was led to the staion in Budapest by the miltary police after it was claimed that he stole the hen, and had hit István with it so he got a blue eye. Švejk denied this, they had only been argueing about the price. In the end he got away with paying ten guilders, five for the hen and five for the blue eye.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Veliteli 11. marškumpanie N pochodového praporu 91. pěšího pluku k dalšímu řízení.

Předvádí se pěšák Švejk Josef, dle udání ordonance téže marškumpanie N pochodového praporu 91. pěšího pluku, pro zločin loupeže, spáchaný na manželích Istvánových v Išatarča v rayoně velitelství nádraží.

| Lathe operator Matějů |  | |||

| |||||

Matějů var a lathe operator mentioned when Švejk pulls a story to illustrate that hitting Mr. István with the hen is very little to make a fuzz about.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] To vyrazili ,U starý paní’ soustružníkovi Matějů celou sanici cihlou za dvacet zlatejch, s šesti zubama, a tenkrát měly peníze větší cenu než dnes. Sám Wolschläger věší za čtyry zlatky.

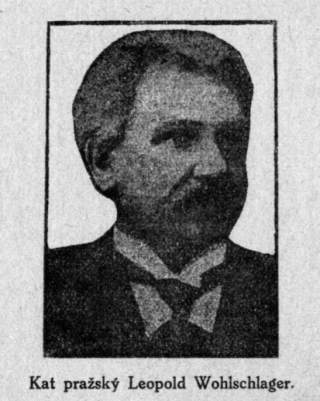

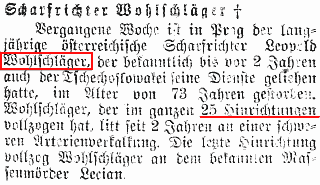

| Wohlschlager, Leopold |  | |||

| *1.11.1855 Osijek - †21.8.1929 Praha | |||||

| |||||

Podzemní Praha, , 1929

, 30.8.1929

, 21.8.1929

Wohlschlager is mentioned when Švejk pulls a story to illustrate that the price Mr. István demanded for the hen in Budapest was extortionate. Wohlschlager did after all hang people for only four guilders.

Background

Wohlschlager (sometimes written Wohlschläger) was the public executioner in Bohemia from 1888. He was as a fifteen-year old present at the execution of gipsy Janeček in 1871, the last public execution in Böhmen during the reign of Austria-Hungary. The execution was carried out by his step-father Jan Piperger.

He continued as official executioner in Czechoslovakia from 1918 until his death. When he wasn't carrying out his official duties, he worked as a goldsmith in Příčná ulice. In the address book for Prague (1910) he is listed as "executioner", in the population registry as goldsmith and executioner.

Švejk's assertion that he was paid 4 guilders for each execution is not correct; Wohlschlager received 25 already from the beginning. When he wasn't carrying out his official duties, he worked as a goldsmith in Příčná ulice. In 1929, the year he died, he even had a book published: Ve službách spravedlnosti za Rakouska i Republiky (Serving justice in Austria and in the Republic). He died at his home at Letná after having been ill with arteriosclerosis for two years.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] To vyrazili ,U starý paní’ soustružníkovi Matějů celou sanici cihlou za dvacet zlatejch, s šesti zubama, a tenkrát měly peníze větší cenu než dnes. Sám Wohlschläger věší za čtyry zlatky.

Credit: Karel Ladislav Kukla, Egon Erwin Kisch

Also written:WohlschlägerHašek

Literature

- Soupis pražských domovských příslušníků 1830-1910 (1920),

- Prager Pitaval, ,1931

- Leopold Wohlschlager,

- Podzemní Praha, ,1929

- Leopold Wohlschlager, ,9.1.1923

- Populární kat, který zemřel ve středu v Praze, ,24.8.1929

| Mourková |  | |||

| |||||

Mourková was an abandoned lady from Praha II. who together with Šousková raped an impotent geriatric by Roztoky.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] “Vona je to holt vášeň, ale nejhorší je to, když to přijde na ženský. V Praze II byly před léty dvě vopuštěný paničky, rozvedený, poněvadž to byly coury, nějaká Mourková a Šousková, a ty jednou, když kvetly třešně v aleji u Roztok, chytly tam večer starýho impotentního stoletýho flašinetáře a vodtáhly si ho do roztockýho háje a tam ho znásilnily

| Šousková |  | |||

| |||||

Šousková was an abandoned lady from Praha II. who together with Mourková raped an impotent geriatric by Roztoky.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] “Vona je to holt vášeň, ale nejhorší je to, když to přijde na ženský. V Praze II byly před léty dvě vopuštěný paničky, rozvedený, poněvadž to byly coury, nějaká Mourková a Šousková, a ty jednou, když kvetly třešně v aleji u Roztok, chytly tam večer starýho impotentního stoletýho flašinetáře a vodtáhly si ho do roztockýho háje a tam ho znásilnily

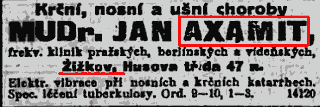

| Professor Axamit, Jan |  | |||

| *12.12.1870 Rychnov nad Kněžnou - †18.11.1931 Praha | |||||

| |||||

,1927

,6.4.1912

,21.8.1924

Axamit from Žižkov got involved by chance in the rape story of the ladies Mourková and Šousková.

Background

Axamit was a Czech medical doctor, specialising in ear, nose and throat. After completing his studies at a university in Prague, he worked as a medical assistant in Prague, Berlin and Vienna. Later he returned and opened his own consultancy in Žižkov.

He was also a self taught archaeologist, the theme of this grotesque anecdote. During World War I he was briefly head the Prehistoric Department of the National Museum and from 1918 he worked as a conservationist for National Heritage. Over the years he became far better known as a archaeologist than a medic.

Some Axamit was also the subject of the short-story Vláda je vinná (The government is guilty) by Jaroslav Hašek from 1911, printed in Rovnost. The author probably had another Axamit in mind: he referred to an official at the Governor's Office (k.k. Statthalterei).

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] To je na Žižkově pan profesor Axamit a ten tam kopal, hledal hroby skrčenců a několik jich vybral, a voni si ho, toho flašinetáře, vodtáhly do jedný takový vykopaný mohyly a tam ho dřely a zneužívaly. A profesor Axamit druhej den tam přišel a vidí, že něco leží v mohyle.

Credit: Jaroslav Šerák, Hans-Peter Laqueur

Literature

- Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství, ,1851 - 1914

- Vláda je vinná, Jaroslav Hašek,10.7.1911

- MUDr. Axamit zemřel, ,20.11.1931

| Feldwebel Nasáklo |  | |||

| |||||

Nasáklo was a sergeant from the 12th march company, a tyrant, who on orders from Hauptmann Ságner gave Švejk rifle drill as punishment for giving Offiziersdiener Baloun exercise drills after he had tried to tuck away a chicken leg.

On departure from Budapest it is revealed that Nasáklo was left behind, haggling with a prostitute behind the station.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Batalionní ordonanc obdržel rozkaz zavolat šikovatele od 12. kumpanie Nasákla, který byl znám jako největší tyran, a zaopatřit ihned Švejkovi ručnici. „Zde tento muž,“ řekl hejtman Ságner k šikovateli Nasáklovi, „nechce zbytečně proválet drahocenný čas. Vezměte ho za vagon a hodinu s ním cvičte kvérgrify. Ale beze všeho milosrdenství, bez oddychu. Hlavně pěkně za sebou, setzt ab, an, setzt ab!

| Oberleutnant Kvasnička |  | |||

| |||||

Kvasnička was a senior lieutenant at the Karlín garrison who could promise the recruits hell also in their next life, all according to Švejk. The point is driven home by an impressive volley of expletives.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] K tomuto připojil Švejk tuto jednoduchou poznámku: „Ba jo, žádnej člověk neví, co bude vyvádět za pár milionů let, a ničeho se nesmi vodříkat. Obrlajtnant Kvasnička, když jsme ještě sloužívali v Karlíně u erkencunkskomanda, ten vždycky říkal, když držel školu: ,Nemyslete si, vy hovnivárové, vy líní krávové a bagounové, že vám už tahle vojna skončí na tomhle světě. My se ještě po smrti uhlídáme, a já vám udělám takovej vočistec, že z toho budete jeleni, vy svinská bando.’“

| Adjutant Ziegler |  | |||

| |||||

Ziegler was a skinny battalion aide who would hardly make up a portion for one march company according to Švejk.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.2] Jakpak se jmenuje, pane rechnungsfeldvébl, ten náš adjutant od našeho batalionu? Ziegler To je ňákej takovej uhejbáček, z toho by se neudělaly porce ani pro jednu marškumpačku.“

|

III. The famous thrashing |

| |

2. In Budapest | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 8.11.2024 |