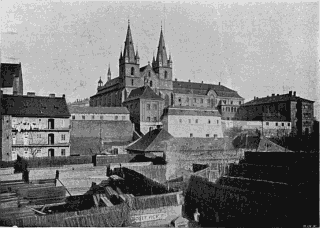

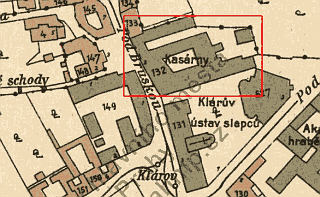

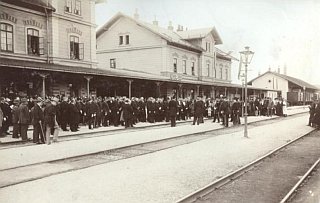

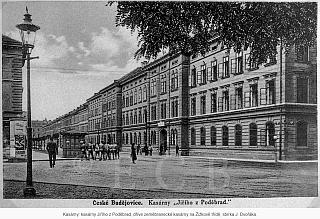

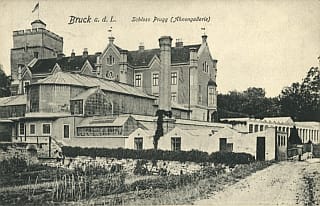

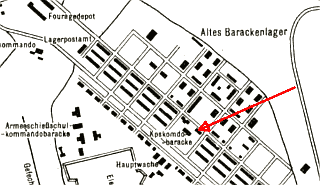

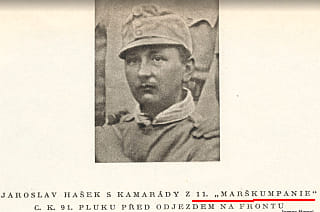

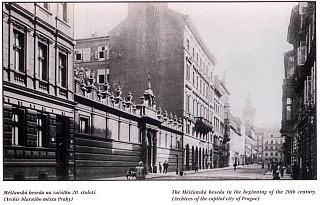

Mariánská kasárna in CB (Budweis). Until 1 June 1915 it was the home of the Good Soldier Švejk's Infanterieregiment Nr. 91. In 1915 Jaroslav Hašek also served with the regiment in these barracks.

The novel The Good Soldier Švejk refers to a number of institutions and firms, public as well as private. On these pages they were until 15 September 2013 categorised as 'Places'. This only partly makes sense as this type of entity can not always be associated with fixed geographical points, in the way that for instance cities, mountains and rivers can. This new page contains military and civilian institutions (including army units, regiments etc.), organisations, hotels, public houses, newspapers and magazines.

The line between this page and "Places" is blurred, churches do for instance rarely change location, but are still included here. Therefore Prague and Vienna will still be found in the "Places" database, because these have constant coordinates. On the other hand institutions may change location: Odvodní komise and Bendlovka are not unequivocal geographical terms so they will from now on appear on this page.

The names are colour coded according to their role in the plot, illustrated by these examples: U kalicha as a location where the plot takes place, k.u.k. Kriegsministerium mentioned in the narrative, Pražské úřední listy as part of a dialogue, and Stoletá kavárna, mentioned in an anecdote.

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (286)

Show all

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (286)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38)

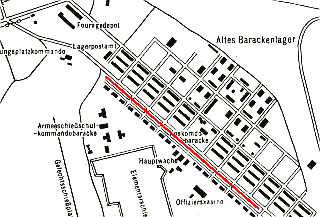

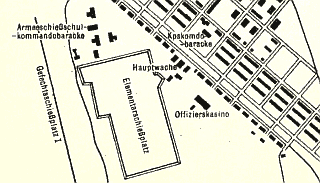

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44) 4. New afflictions (26)

4. New afflictions (26)

|

I. In the rear |

| |

Introduction | |||

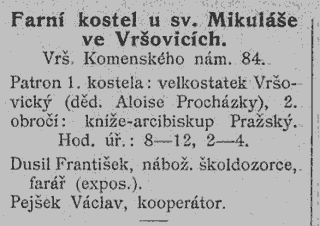

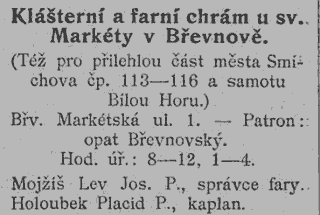

| Temple of Artemis |  | |||

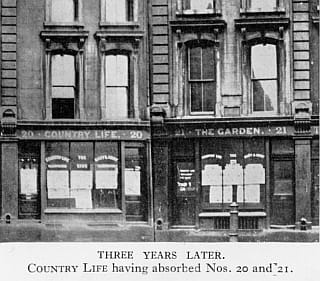

| |||||

Výbor ze spisů Xenofontových, ,1880

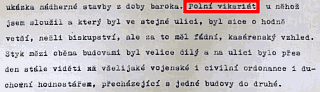

Temple of Artemis is mentioned indirectly in the author's description of Herostratus, "he who set fire to the temple of the goddess in Ephesus".

Background

Temple of Artemis was a temple in Ephesus, regarded as one of the seven wonders of the world. It was raised in the honour of the goddess Artemis. The temple burnt down in 356 BC (Herostatos), but was rebuilt after. Today there are only ruins left.

Quote(s) from the novel

[Úvod] On nezapálil chrám bohyně v Efesu, jako to udělal ten hlupák Herostrates, aby se dostal do novin a školních čítanek.

Also written:Artemidin chrámczTempel der Artemisde

|

I. In the rear |

| |

1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war | |||

| Drogerie Průša |  | |||

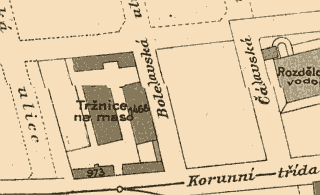

| Královské Vinohrady/699, Tylovo nám. 19 | |||||

| |||||

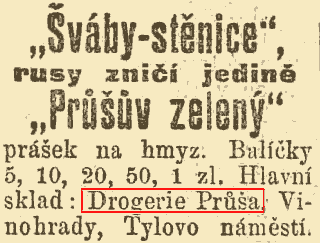

,24.6.1903

,6.5.1910

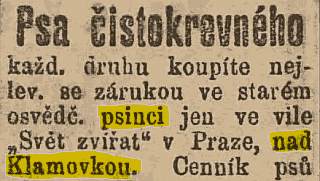

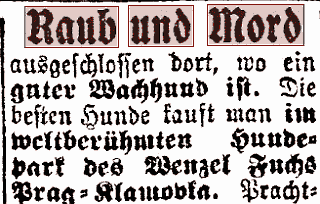

Drogerie Průša was the chemist's store where the first sluha u Průši Ferdinand was an assistant. He drank a bottle of hair oil by mistake.

Background

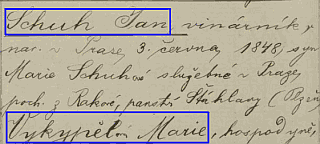

Drogerie Průša was a chemist's store at Tylovo náměstí right on the lower corner with Vávrova třída at Vinohrady. Jaroslav Hašek worked as an apprentice here some time between March 1898 and September 1899.

Over the years several newspaper adverts testify to the existence of the chemist's, confirmed by address book entries. In 1906 discrete newspaper adverts for remedies against "men's problems" appeared, but they also advertised remedies against bed-bugs. In August 1915 an advert appeared in Prager Tagblatt where large amounts of furniture was for sale, indicating that the shop was about to close down. The owner was drogista Průša (František).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Jednoho, ten je sluhou u drogisty Průši a vypil mu tam jednou omylem láhev nějakého mazání na vlasy, a potom znám ještě Ferdinanda Kokošku, co sbírá ty psí hovínka. Vobou není žádná škoda.“

Sources: Jaroslav Šerák, Radko Pytlík

Literature

- Z droguerieJaroslav Hašek24.3.1904

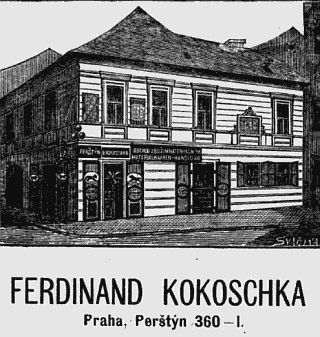

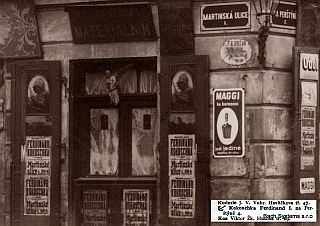

- Ferdinand Kokoška & spol.

- Roboragen21.4.1906

- Průšův prašek zelený7.5.1908

- Verkaufe billig18.8.1915

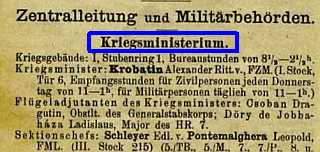

| K.u.k. Heer |  | |||

| Wien I., Stubenring 1 | |||||

| |||||

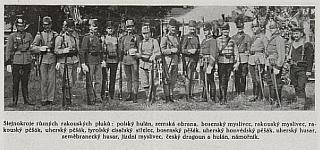

1914

Uniforms of the Austro-Hungarian armed forces.

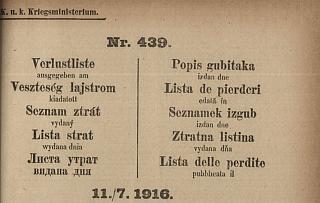

,31.7.1914

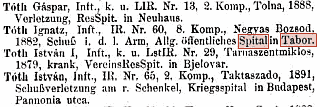

Example of a casualty list

,11.7.1916

K.u.k. Heer is first mentioned (as "the army") in an anecdote Švejk tells from his time doing compulsory military service. This is in the conversation with Mrs. Müllerová at the very start of The Good Soldier Švejk. After this the army is mentioned innumerable times, and is the most important backdrop for the novel where Švejk is a soldier) from the middle of Part One. The army is also the principal target of Hašek's satire.

Background

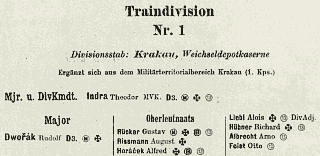

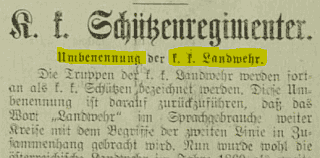

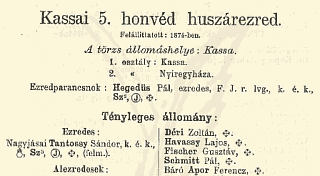

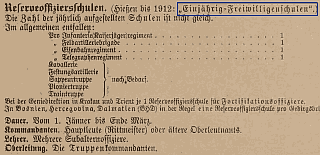

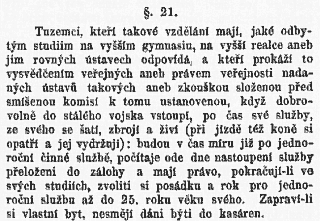

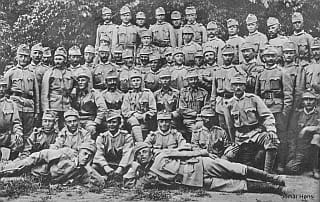

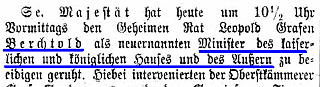

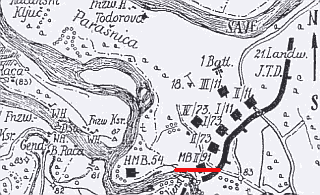

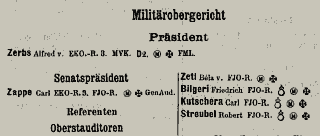

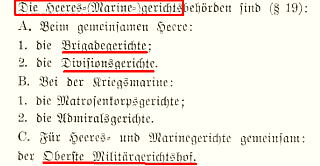

K.u.k. Heer (also called k.u.k. Armee or Gemeinsame Armee) was the largest and most important body in k.u.k. Wehrmacht. Together with the k.k. Landwehr (Austrian national guard) and the Honvéd (Hungarian national guard) it made up the Landstreitkräfte (terrestrial forces). These and the k.u.k. Kriegsmarine (navy) made up the total armed forces of the Dual Monarchy.

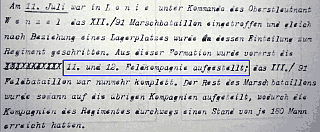

The common army consisted of infantry, cavalry, artillery, supply-troops and technical troops. The period of service was until 1912 three years, then two. During the war, losses were replaced by so-called march battalions, one of which Švejk was later to be assigned to. The common army existed from 1867 to 1918 and suffered disastrous losses in World War I, the only full-scale war it ever participated in. At various time it fought on four fronts; Serbia, Galicia, Romania and Tyrol and after the heavy losses in 1914 it became increasingly dependant on German support.

The army command was from 1913 located in the building of the k.u.k. Kriegsministerium at Stubenring 1, Vienna. At the time when Švejk did his military service they were surely still at the old premises in Am Hof 2. This building was demolished in 1912.

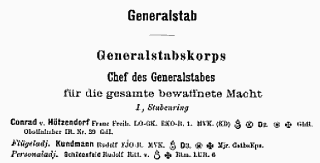

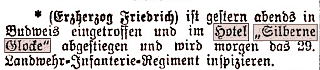

Oberbefehl formally lay with the monarch who communicated with the army through Militärkanzlei Seiner Majestät des Kaisers und Königs. Kriegsministerium was responsible for the day to day operation of the army. From 1914 to 1917 Archduke Friedrich was general inspector of the army but he delegated the operative responsibility to field marshal Feldmarschall Conrad.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Jó, paní Müllerová, dnes se dějou věci. To je zas ztráta pro Rakousko. Když jsem byl na vojně, tak tam jeden infanterista zastřelil hejtmana. Naládoval flintu a šel do kanceláře.

Also written:Austro-Hungarian ArmyenRakousko-uherská armádaczAusterrike-Ungarns Hærno

Literature

- Schematismus für das k.u.k. Heer (s. 50)1914

- Veltzés Internationaler Armee-Almanach1914

- The First World War and the end of the Dual Monarchy2014

- 1914 - 2014, 100 Jahre erster Weltkrieg

- Handbuch für den Infanteristen des k.u.k. Heeres, sowie der k. k. Landwehr1914

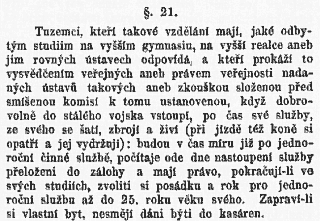

- Zákon branný1869

- Branná moc v míru i ve válce1914

- Österreich-Ungarns bewaffnete Macht 1900 - 1914

- Die Österreichisch-Ungarische Armee 1914 - 1918

- Zentralleitung und Militärbehörden

- Die Gesamtverluste ...

- Unteilbar und Untrennbar1917

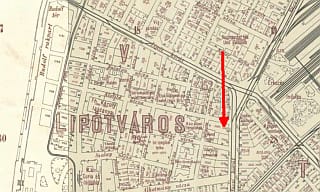

| U kalicha |  | |||||

| Praha II./1732, Na Bojišti 14 | |||||||

| |||||||

,11.11.1923

,2.8.1899

,7.11.1913

,17.11.1917

,14.11.1923

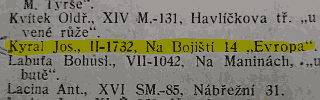

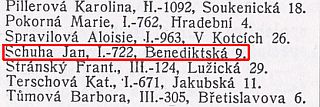

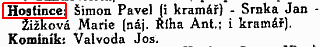

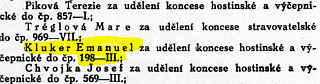

Chytilův adresář hl. města Prahy,1924

U kalicha is mentioned 17 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

U kalicha is the tavern where Švejk and pubkeeper Palivec were arrested by detective Bretschneider at the very start of the novel. This probably happened on 29 June 1914 as the news about the murders in Sarajevo appeared in the newspapers on that day (Mrs. Müllerová had just read about it).

The plot returns to U kalicha in [I.6] when Švejk is released from his ordeal, again meets detective Bretschneider, and convinces the detective to buy dogs from him. His last visit is in [I.10,4] after he has started his career as officer's servant with Feldkurat Katz. Mrs. Palivcová refuses to serve him as she thinks he is a deserter.

U kalicha is also mentioned in [II.4] in the classic scene from Bruck when Švejk and Sappeur Vodička promise to meet there after the war, at six in the evening - one of the most famous quotes from the entire novel. Here Švejk reveals that U kalicha served beer from Velké Popovice.

Background

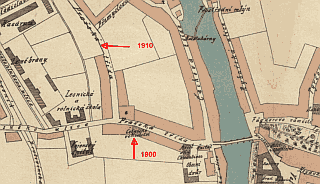

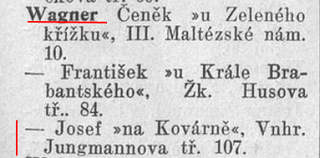

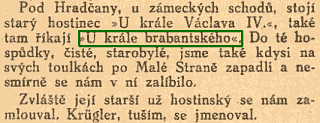

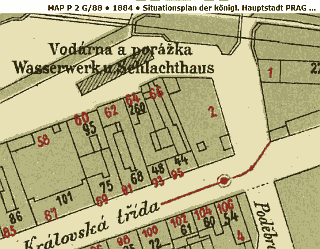

U kalicha is the name of a restaurant in Na Bojišti street in Nové město, and also the name of the building where the restaurant is located. Today it is, thanks to The Good Soldier Švejk, a major tourist attraction, but in 1914 it was an ordinary pub with one tap-room. Proofs of the tavern's existence appear already in 1896 when Vilém Šubert is listed as landlord at Na Bojišti 8. In 1899 adverts reveal that it already then was known as U kalicha and that it was located in Na Bojišti 1732/8, in the same building as today. That year the owner was trying to sell new bicycles, presumably as a side business. The building has existed since 1890 or slightly earlier. In 1907 the property was advertised for sale and the advert even mentioned the pub.

In the 1910 address book it is listed at Na Bojišti 1732/14. The landlord is now Vilém Juris, who in 1907 is registered as landlord of a pub in Smíchov. Police records reveal that he lived at Na Bojišti 1732 from 18 July 1908, was born in 10 June 1871 and married to Blahoslava. In 1913 he placed adverts specifically aimed at students and he used the name U zlatého kalichu. Juris marketed his establishment "as a well known meeting spot for students, with concerts every day and open until the morning". In 1917 some Vaneček had taken over the license. In April 1923 adverts reveal that the pub had been renamed Café Evropa and offered French cuisine, and the 1924 address book lists the owner as Josef Kyral. Adverts from November 1923 show signs that U kalicha had started to exploit its connection to The Good Soldier Švejk.

Hašek and U kalicha, an unclear connection

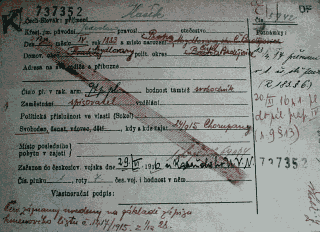

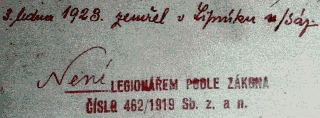

© VÚA

A blip from Elsbeth Wessel

It remains unclear why Jaroslav Hašek gave U kalicha such a prominent role in the novel as none of his biographers or friends mentions it as a place he frequented. Nor do we have been able to confirm that they actually served beer from Velké Popovice but as this was the largest producer in all of Bohemia there is every reason to believe that Švejk is right.

One possible connection is one Josef Švejk (1892-1965) who from 1912 onwards lived two houses down the street. This is a person the author may have known about, particularly since both were volunteers in České legie from 1916. In this context it is worth mentioning that there is no mention of U kalicha in the 1911 and 1917 versions of The Good Soldier Švejk so the author's knowledge of this person may indeed have inspired Hašek to introduce U kalicha in the novel. The soldier's first name Josef is also introduced for the first time in the novel from 1921.

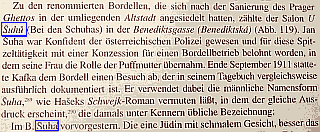

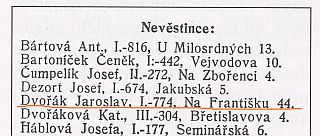

We also know that Jaroslav Hašek associated with students from the technical college so he may have been drawn to U kalicha by them. That he knew the environs of U kalicha is also clear. Two houses down, in number 463/10, a brothel was registered on Antonín Nosek (1912). This could explain why Švejk told Sappeur Vodička that "they have girls there".

The well known Norwegian germanist Elsbeth Wessel contributes a most peculiar item. In an otherwise insightful chapter on Hašek she informs that "that the author slowly drank himself to death at U kalicha". Who the source of this nonsense is we don't know, but this should be regarded as a blip as the rest of her contribution is of high quality.

Legends forming

,5.12.1929

Over the years a number of legends have been spun around U kalicha and Jaroslav Hašek’s novel. An early example is Maxmilian Huppert[a] who claimed that a certain František Švejca (born 1875) was a regular there, traded in stolen dogs, and adds a number of details that bear the hallmarks of trying to adapt reality to fit the novel. Hupperts crown witness is a former landlord at U kalicha, Ferdinand Juris. He claims to have known this "Švejk". More tangible is the information that U kalicha no longer operated and that the premises now were used for storing flour.

In 1968 a related story appeared in the weekly magazine Květy (12 September 1968, signed J.R Veselý). It contained sensational claims that a Josef Švejk was in fact a friend of Jaroslav Hašek and that they met on several occasions before, during and after the war. Much of the story has been verified, but the details that attempt to connect this Švejk to Hašek appears to be invented. See Josef Švejk for details.

A web of hearsay

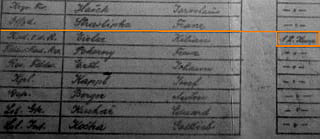

In his book Die Abenteuer des gar nicht so braven Humoristen Jaroslav Hašek (1989) Jan Berwid-Buquoy threw in several new but rather "colourful" items. It is claimed that a Marie Müllerova was a brothel madam in the same building, that František Strašlipka, the alleged model for Švejk, was a regular there and was even her lover, that Palivec was a waiter there, that the landlord was a certain foul-mouthed Václav Šmíd. The author has since re-spun and expanded the story a few times, through another book (2011) and an article in Reflex (2012). He even changed the name of the landlord and other details, but the essence of the information has not been possible to confirm. Later it was claimed that Anastasie Herzog bought the building in 1907. Police records show that the businessman Benno Herzog actually lived in the building in 1912, but the only Anastasie Herzog showing up in police records was his daughter, born in 1907! The 1906 address books lists the owner of the building U kalicha as Karel Císař.

In the end these stories appear to be based on hearsay. A more serious concern is that most it appears on the restaurant's own website (even in English and Russian), so the myths get propagated world-wide. Here even more "facts" are thrown in the pot: U kalicha is supposed to have become popular after the translation of The Good Soldier Švejk into German (1926) and particularly during the thirties when German journalists and men of letter came to visit Egon Erwin Kisch. In that case they would have been disappointed because the restaurant closed down some time between 1924 and 1929[a] (it is not present in the 1936 address book).

A tourist attraction

The original tap-room at No. 14 (2011)

Around 1955 U kalicha was expanded (probably re-opened), and deliberately turned into a tourist attraction. From then on the restaurant occupies both No 14. and No 12. It lives well on the connection with The Good Soldier Švejk, with prices above average and frequent tour groups visiting. Still U kalicha is worth a visit as it is decorated with memorabilia related to Švejk and the times of World War I. To avoid the crowds it is advisable to visit around lunchtime or early afternoon. The food is Czech, the menu comes in 27 languages!

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Já teď jdu do hospody „U kalicha“, a kdyby sem někdo přišel pro toho ratlíka, na kterýho jsem vzal zálohu, tak mu řeknou, že ho mám ve svém psinci na venkově, že jsem mu nedávno kupíroval uši a že se teď nesmí převážet, dokud se mu uši nezahojí, aby mu nenastydly. Klíč dají k domovnici.“

[I.1] V hospodě U kalicha seděl jen jeden host. Byl to civilní strážník Bretschneider, stojící ve službách státní policie. Hostinský Palivec myl tácky a Bretschneider se marně snažil navázat s ním vážný rozhovor.

[I.1] A Švejk opustil hospodu U kalicha v průvodu civilního strážníka...

[I.1] Když vcházeli do vrat policejního ředitelství, řekl Švejk: "Tak nám to pěkně uteklo. Chodíte často ke Kalichu?" A zatímco vedli Švejka do přijímací kanceláře, u Kalicha předával pan Palivec hospodu své plačící ženě, těše ji svým zvláštním způsobem: "Neplač, neřvi, co mně mohou udělat kvůli posranýmu obrazu císaře pána?"

[I.1] Jestli situace vyvinula se později jinak, než jak on vykládal u Kalicha, musíme mít na zřeteli, že neměl průpravného diplomatického vzdělání.

[I.5] Nedávno u Kalicha nevyvedl jeden host nic jinýho, než že sám sobě rozbil sklenicí hlavu.

[I.6] Jeho uvažováni, má-li se stavit napřed ještě u Kalichu, skončilo tím, že otevřel ty dveře, odkud vyšel před časem v průvodu detektiva Bretschneidra.

[I.10.4] Pak se šel Švejk podívat ke Kalichu. Když ho paní Palivcová uviděla, prohlásila, že mu nenaleje, že asi utekl.

[I.16] Ceremoniář dr. Guth mluví jinak než hostinský Palivec u Kalicha a tento román není pomůckou k salónnímu ušlechtění a naučnou knihou, jakých výrazů je možno ve společnosti užívat. Jest to historický obraz určité doby.

[II.3] Jeden medik, který chodíval ke Kalichu, nám jednou vykládal, že to ale není tak jednoduchý.

[II.4] Když se Švejk s Vodičkou loučil, poněvadž každého odváděli k jejich části, řekl Švejk: "Až bude po tý vojně, tak mé přijel navštívit. Najdeš mé každej večer od šesti hodin u Kalicha na Bojišti."

[II.4] Potom se vzdálili a bylo slyšet zas za hodnou chvíli za rohem z druhé řady baráků hlas Vodičky: "Švejku, Švejku, jaký mají pivo u Kalicha?" A jako ozvěna ozvala se Švejkova odpověď: "Velkopopovický."

Also written:At the ChaliceenZum Kelchde

Literature

- Šubert Vilém1896

- Vilém Juris

- Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství1851 - 1914

- Pokoj12.11.1890

- Leštitelka6.9.1892

- Kolo7.5.1899

- Prodá se dům13.7.1907

- Kavárna U zlatého kalichu7.11.1913

- Zřisení kapely z vojenských invalidů8.10.1917

- Chytilův adresář hl. města Prahy1924

- Románové restaurační a jiné zábavní podniky2009 - 2021

- Osudy záhadného hostince U kalicha aneb Jak to vlastně bylo doopravdy?2.5.2012

- Povídání o Frantovi Strašlipkovi

- Between legends and reality

- Mezi legendou a skutečností

| a | Historisches vom Švejk | 5.12.1929 |

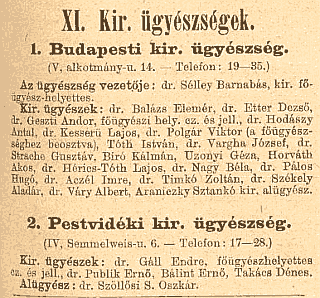

| Staatspolizei |  | |||

| Praha I./313, Bartolomějská 4 | |||||

| |||||

© LA-PNP

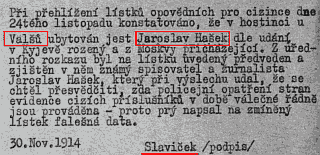

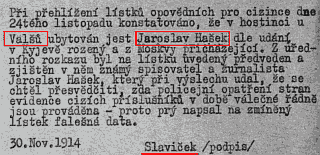

Hašek's encounter with state police after having registered as a Russian trader at U Valšů, 24 November 1914.

© LA-PNP

,21.8.1916

Staatspolizei is mentioned when it is revealed that detective Bretschneider is in the service of the state police.

Background

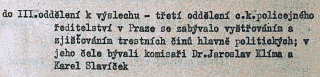

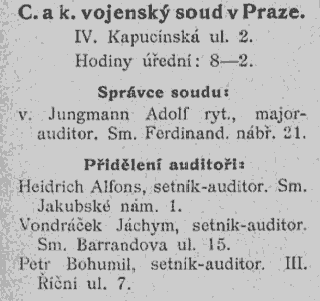

Staatspolizei (officially k.k. Staatspolizei) was the domestic civilian intelligence service of Cisleitanien, which main task was surveillance of potential enemies of the state. In the context of The Good Soldier Švejk we understand the Prag branch. The department was created in 1893 after civilian unrest and the unit reported directly to the "Statthalter" (Governor). In Prague their servicemen and agents were operating from the premises of c.k. policejní ředitelství. In their service were amongst others two young lawyers, Mr. Slavíček and Mr. Klíma. Head of the unit was Viktor Chum.

U Valšů

Jaroslav Hašek had intimate knowledge of the state police, originating from his period as an anarchist activist (from 1904). His most celebrated encounter with them was after his famous hoax at U Valšů on 24 November 1914 where he registered as a Russian trader, ostensibly to test the vigilance of the Austrian security service. He was let off with only 5 days in jail which he served immediately.

During the war

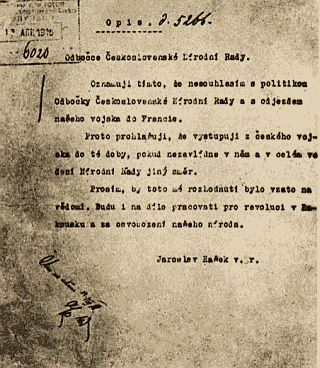

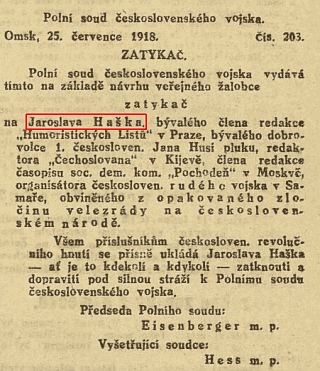

During the war the eyes of the state police again fell on Jaroslav Hašek. It happened after the author on 17 June 1916 published a story in Čechoslovan where he lets a tomcat soil pictures of the emperor. This led to charges of high treason and an arrest order was issued. Several of the other stories he wrote also aroused interest at home. They were translated to German for the benefit of the investigators and led to a lively exchange between the police headquarters in Prague and Vienna.

Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí

… Švejka vedli k výslechu do oddělení státní policie přímo k policejnímu komisaři Klímovi a Slavíčkovi.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] V hospodě „U kalicha“ seděl jen jeden host. Byl to civilní strážník Bretschneider, stojící ve službách státní policie. Hostinský Palivec myl tácky a Bretschneider se marně snažil navázat s ním vážný rozhovor.

Literature

- Pražské policejní ředitelství, jeho Státní(politická) policie a její informátoři …Zdeněk Kárník

- Za pana Drašnera

- Viktor Chum2018 - 2023

- Povídka o obrazu císaře Františka Josefa I.Jaroslav Hašek17.7.1916

- Po stopách státní policie v PrazeJaroslav Hašek21.8.1916

- Bašta germanisace3.12.1917

| Vinárna Sarajevo |  | |||

| |||||

Vinárna Sarajevo was a wine tavern in Nusle where, according to pubkeeper Palivec, there was fighting every day.

Background

Vinárna Sarajevo has yet to be identified. According to Milan Hodík pubkeeper Palivec may have referred to a small pub known as Bosna in Michle[a].

Milan Hodík

Šlo nejspíš o malou hospodu zvanou Bosna na michelském kopce nad Bondyho statkem.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] „Ty nám to pěkně v tom Sarajevu vyvedli,“ se slabou nadějí ozval se Bretschneider. „V jakým Sarajevu?“ otázal se Palivec, „v tej nuselskej vinárně? Tam se perou každej den, to vědí, Nusle.“

| a | Encyklopedie Švejka II. díl | 1998 |

| Mladočeši |  | ||||

| Praha II./1987, Ferdinandova tř. 20 | ||||||

| ||||||

Karel Kramář, party chairman for many years.

,20.7.1917

Mladočeši is mentioned indirectly when pubkeeper Palivec tells detective Bretschneider that he serves whoever pays up, and that he didn't care at all if it was a Muslim, anarchist, Turk or a Young Czech who killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

Background

Mladočeši (the Young Czechs Party) - officially Národní strana svobodomyslná (the National Liberal Party), was a Czech political party that existed from 1874 to 1918. The party reached its zenith after 1890. Due to their for the time radical demands on universal suffrage and greater autonomy for the Czech lands of Austria-Hungary, they received considerable support in their homeland but faced correspondingly greater opposition from Vienna.

Thereafter the Social Democrats and the Agrarian Party made inroads into their electoral base, and the party lost much of its influence. The leading politician in the history of the party was Kramář. The party's official newspaper was Národní listy, to which Jaroslav Hašek contributed many short stories. At the 1911 election to Reichsrat they achieved 9.8 per cent of the votes in Bohemia and had 14 representatives.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] „Host jako host,“ řekl Palivec, „třebas Turek. Pro nás živnostníky neplatí žádná politika. Zaplať si pivo a seď v hospodě a žvaň si, co chceš. To je moje zásada. Jestli to tomu našemu Ferdinandovi udělal Srb nebo Turek, katolík nebo mohamedán, anarchista nebo mladočech, mně je to všechno jedno.“

Also written:Young Czech PartyenJungtschechendeUngtsjekkaraneno

Literature

| Věznice Pankrác |  | ||||

| Nusle/88, Palackého tř. - | ||||||

| ||||||

Bohemia,7.10.1913

Věznice Pankrác is implicitly mentioned by pubkeeper Palivec when he explains that talking politics might mean ending up in Pankrác.

The prison is also referred to in [I.3] where the unfortunate lathe operator who broke into Podolský kostelík was incarcerated and later died.

Background

Věznice Pankrác (c. k. trestnice pro mužké v Praze) was at the time a large jail for men, and "pankrác" is almost synonymous with prison in Czech slang. The prison is named after the Pankrác district where it is located. Construction started in 1885 and was completed in 1889.

It was at the time a modern prison with good conditions for the inmates. In Austrian times it mostly housed dangerous male criminals but also saw the odd political prisoner.

The prison later became the scene of executions and 1580 persons were killed; 1087 of them during the Nazi occupation. During Communist rule from 1948 another few hundred were executed.

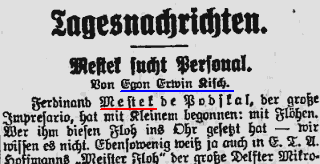

Egon Erwin Kisch

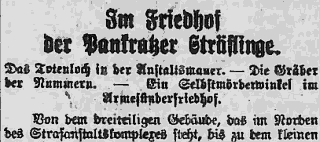

The Raging Reporter has contributed his part to the fame of the prison. Denied permission to enter, he still climbed the walls, and reported from the cemetery of the inmates. Their graves were not marked! This is all revealed in the story Im Friedhof der Pankratzer Sträflinge (On the cemetery of the Pankrác inmates), first printed in Bohemia before the war [a], in 1931 appearing in the book Prager Pivatal with the title changed.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] „Já se do takových věcí nepletu, s tím ať mi každej políbí prdel,“ odpověděl slušně pan Palivec, zapaluje si dýmku, „dneska se do toho míchat, to by mohlo každému člověku zlomit vaz. Já jsem živnostník, když někdo přijde a dá si pivo, tak mu ho natočím. Ale nějaký Sarajevo, politika nebo nebožtík arcivévoda, to pro nás nic není, z toho nic nekouká než Pankrác.“

[I.3] Potom ten soustružník zemřel na Pankráci.

Also written:Pankrác PrisonenPankratz GefängnisdePankrác fengselno

Literature

- The inside story of the history of Prague’s Pankrác prisonChris Johnstone2010

- Zu Besuch bei toten SträflingenEgon Erwin Kisch2010

| a | Im Friedhof der Pankratzer Sträflinge | Egon Erwin Kisch | 7.10.1913 |

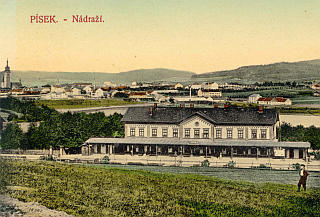

| Krajský soud Písek |  | |||

| Písek/121, Velké nám. 17 | |||||

| |||||

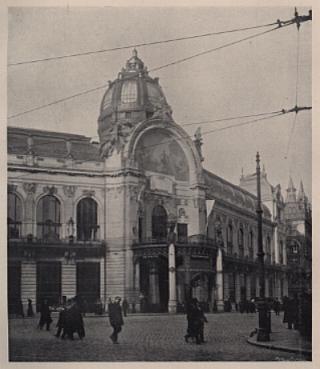

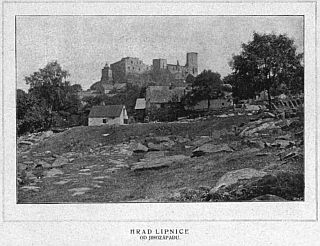

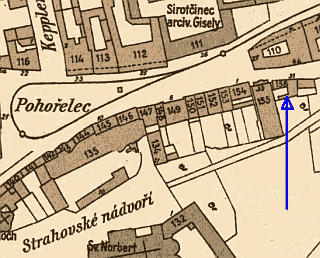

Velké náměstí in Písek (1917). The large building to the left housed the regional court.

© Písecký deník

Královské město Písek, , 1898

Krajský soud Písek is where the pig gelder from Vodňany was sentenced and executed, all whilst uttering the worst imaginable things about the emperor. At least this is what Švejk tells detective Bretschneider at U kalicha.

Background

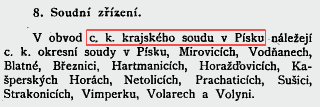

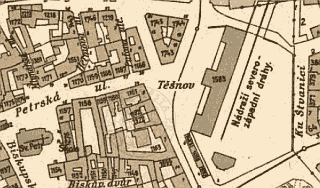

Krajský soud Písek was an institution that was part of the judiciary of Austria, and also remained functional in Czechoslovakia until 1945. It resided in a large building at southern part of Velké náměstí, down towards Otava and adjacent to the smaller Okresní soud Písek. The court president in 1915 was František Soukup. At the site is today (2021) located the latter, i.e. the district court, is but the building is newer.

Hilsner

The court in Písek hosted the 2nd trail of the infamous Hilsner affair (or Polna affair) where the young Jew Leopold Hilsner was accused of ritual murder. His death-sentence was confirmed in Písek on 14 November 1900 but was converted to life imprisonment by Emperor Franz Joseph I. and in 1918 he was set free during a general amnesty[a]. Future president Professor Masaryk put his academic career at stake during his defence of Hilsner, and an article he wrote in on the case was confiscated[b]. The verdict at Písek was quashed as late as 1998.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Když ho potom u krajského soudu v Písku věšeli, ukousl knězi nos a řekl že vůbec ničeho nelituje, a také řekl ještě něco hodně ošklivého o císařovi pánovi.“

Also written:Písek Regional CourtenKreisgericht PísekdeKretsretten Písekno

Literature

- Hilsner byl odsouzen k smrti u píseckého soudu. Ve vězení strávil 18 let.Libuše Kolářová2.11.2016

| b | Bericht über die Revision der Polnaer Processes | Tomáš Masaryk | 10.11.1900 |

|

I. In the rear |

| |

2. The good soldier Švejk at police headquarters | |||

| C.k. policejní ředitelství |  | |||||

| Praha I./313, Ferdinandová třída 15 | |||||||

| |||||||

,13.9.1928

Like the author in the novel Břetislav Hůla (1950) mixes up the 3rd department with the State Police

,1911

C.k. policejní ředitelství was where was Švejk was led by detective Bretschneider after his arrest at U kalicha. He was accused of high treason, insulting His Majesty, and even sedition - accusations he agreed to without flinching. He stayed at police HQ through the whole of [I.2], a chapter which took place in the course of just one evening/night. In the morning he was taken to c.k. zemský co trestní soud in a police car which left through the main gate, i.e. in ul. Karoliny Světlé 2.

The gate of the building and three places inside are mentioned: the reception, the cells on the first floor and the interrogation room in the 3rd department, up the stairs from the cells but unclear on which floor. Švejk rarely complained, but here he shows his dissatisfaction with the long way from the cell to the interrogators room.

In [I.6] Švejk pays police HQ another visit after he was arrested because of his strikingly enthusiastic reaction to the declaration of war. Her the author delivers his personal opinion of the institution "where the spirit of foreign authority wafted through the building".

Background

C.k. policejní ředitelství (C.k. policejní ředitelství v Praze) was the police HQ in Prague and it's official address in 1914 was Ferdinandova třída 15. The entrance was around the corner in ul. Karoliny Světlé 2. It was (and is) a huge complex, located between Ferdinandova, Karoliny Světlé and Bartolomejská. It is still (2018) the HQ of the Prague's police.

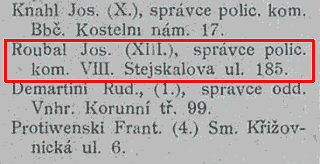

The Police HQ was organised in five departments where the State Police (Staatspolizei), department III (public order), and department IV (safety) are the ones that are relevant in the context of The Good Soldier Švejk. Department III is directly mentioned in the novel, although the author most probably has the State Police Department in mind. In 1913 the following of our acquaintances from the novel were employed: Mr. Slavíček and Mr. Klíma (State Police) and Polizeikommissar Drašner (department IV). Head of the 1st Department was Rudolf Demartini, a person who may have inspired Mr. Demartini, the fat gentleman at c.k. zemský co trestní soud.

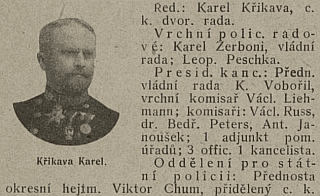

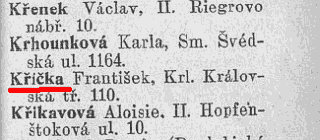

The head of c.k. policejní ředitelství carried the title "Police Director" (from 1912 "Police President") and the position was in the period 1902 to 1915 held by Court Councillor Karel Křikava, uncle of the writer Louis Křikava. He frequented the same environs as Hašek and is mentioned several times in Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona. Head of the State Police Department was Viktor Chum.

Karel Křikava (1860 - 1935) made a rapid career in the police but was pensioned in 1915 for political reasons. He was not informed about the arrest of Kramář and as a result of the conflict that followed he was pensioned due to "health problems". After the war he was reactivated and was given the task of organising the police in Slovakia.

A Russian trader

In November 1915 Jaroslav Hašek acquired first hand knowledge of c.k. policejní ředitelství. As a premeditated provocation he registered at U Valšů as a Russian trader and the State Police soon arrived and arrested the "foreigner".

The good soldier Švejk in captivity

In the second version of The Good Soldier Švejk (Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí), written by Jaroslav Hašek in 1917, police HQ is described in greater detail, particularly the department of Staatspolizei. Bartolomějská ulice is mentioned explicitly and so are the police commissioners Mr. Klíma and Mr. Slavíček and the author correctly notes that both worked for the state police. The description is more elaborate than in the novel and Chum is referred to as head of the "triumvirate".[1]

Švejka vedli k výslechu do oddělení státní policie přímo k policejnímu komisaři Klímovi a Slavíčkovi. Tito dva představitelé aparátu státní policie od vypuknutí války až po objevení Švejka v kanceláři vyšetřili několik set případů udání, provedli spoustu domovních prohlídek a odváděli muže od teplých večeří do Bartolomějské ulice. Jest zajímavé, proč department pražské státní policie právě se usadil v ulici připomínající svým jménem bartolomějskou noc …

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.2] Sarajevský atentát naplnil policejní ředitelství četnými oběťmi. Vodili to jednoho po druhém a starý inspektor v přijímací kanceláři říkal svým dobráckým hlasem: „Von se vám ten Ferdinand nevyplatí!“ Když Švejka zavřeli v jedné z četných komor prvého patra, Švejk našel tam společnost šesti lidí.

[I.6] Budovou policejního ředitelství vanul duch cizí authority, která zjišťovala, jak dalece je obyvatelstvo nadšeno pro válku. Kromě několika výjimek, lidí, kteří nezapřeli, že jsou synové národa, který má vykrvácet za zájmy jemu úplně cizí, policejní ředitelství představovalo nejkrásnější skupiny byrokratických dravců, kteří měli smysl jedině pro žalář a šibenici, aby uhájili existenci zakroucených paragrafů.

[I.10.1] I on, Švejk, byl tenkrát v tom houfu, poněvadž při své smůle řekl komisaři Drašnerovi, když ho vyzval, aby se legitimoval: „Mají na to povolení od policejního ředitelství?“

[II.3] Jako jsem znal jednoho uhlíře, kerej byl se mnou zavřenej na začátku války na policejním ředitelství v Praze, nějakej František Škvor, pro velezrádu, a později snad taky vodpravenej kvůli nějakej pragmatickej sankci.

Also written:Police HeadquartersenPolizeidirektiondePolitihovudkvarteretno

Literature

- C.k. policejní ředitelství v Praze

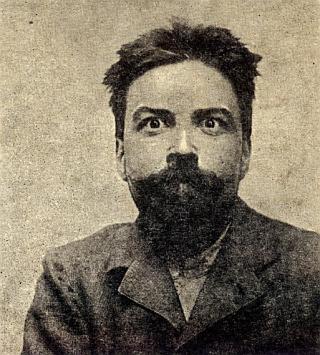

- Český antimilitarism1922

- Rücktritt des Polizeipräsidenten Křikava27.7.1915

- Právo lidu7.8.1915

- Bašta germanisace3.12.1917

- Der erste Polizeipräsident von Prag gestorben24.9.1935

- Pražské policejní ředitelství, jeho Státní(politická) policie a její informátoři …Zdeněk Kárník

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| U Brejšky |  | ||||

| Praha II./107, Spálená ul. 47 | ||||||

| ||||||

,15.5.1884

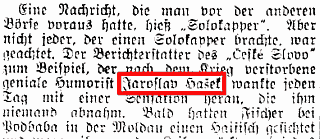

Breaking ice by U Brejšky. Jaroslav Hašek third from the left. Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj is in the middle. The tall man on the left is landlord Karel Brejška.

, 6.2.1914

,19.1.1914

Karel Brejška,1912.

© Národní archiv - Archiv České strany národně sociální

Národní listy,17.5.1923

Egon Erwin Kisch

,6.12.1925

, 1925

U Brejšky was where detective Brixi arrested an unusually fat owner of a paper shop who had bought beer for two Serbian students. The generous man was one of Švejk's inmates in the cell at c.k. policejní ředitelství. The pub is mentioned several times, and in the final chapter it crops up in an anecdote Švejk tells Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek. In this anecdote it is named U Brejsků, a minor change from singular to plural.

Background

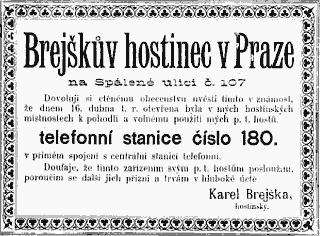

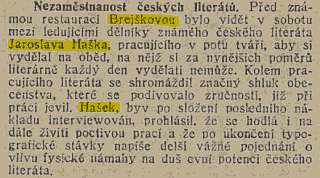

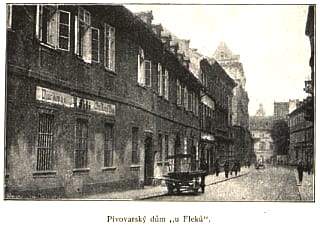

U Brejšky was a restaurant in Spalená ulice in Praha II. that in it's original form existed from 1884 until around 1920. It was known as a meeting place for journalists; Egon Erwin Kisch and others wrote about the phenomenon "news exchange" in Prager Tagblatt in 1925. Both Czech and German newspapermen frequented the place. Immediately after opening the restaurant had installed a telephone station (No. 180), a rare sight in 1884.

The restaurant served beer from Plzeň and was also known for its good food. Not only was it popular amongst journalists: visitors from the province also enjoyed it here. On the first floor it offered meeting rooms and accommodation. U Brejšky (aka. U Brejšků or Brejškova restaurace) was altogether one of the most best known and popular taverns in all of Prague, as indicated by the endless amount of newspaper clips. The restaurant was named after the original owner, Karel Brejška.

Jaroslav Hašek and Brejška

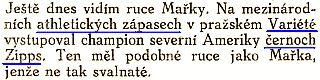

The author The Good Soldier Švejk frequented it regularly and he mentions the restaurant not only in the novel, but also in several of his short stories. Amongst them is Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí (1917) but here it occurs only briefly. On the other hand U Brejšky is the main focus of a story he wrote in 1912 about a meeting with the enormous black American Zipps. The landlord himself appears in the story and is described in positive terms.

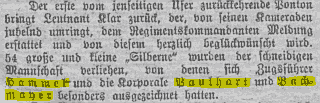

U Brejšky is known from a photo where Jaroslav Hašek and Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj break ice on the street outside. A note in Právo lidu 19 January 1914 indicates that the picture was taken on 17 January 1914 and that it was published with a text on 6 February in Světozor. Both texts refer to a strike amongst typographers. In his memoirs Hájek wrote about Karel Brejška, that the landlord liked Hašek and readily helped him when he was in trouble. Hájek incorrectly dates the picture to the winter of 1912, an error that later propagated into other literature about Hašek. Kuděj confirmed the information about the typographer's strike, that Brejška took pity on the two unemployed literates, and put them to work on writing menu's and breaking ice.

Karel Brejška

The owner of the restaurant was Karel Brejška (6 June 1856 - 15 May 1923), the big man seen to the left on the mentioned photo from Světozor. He bought the building Zlatá váha in Spalená ulice 117/47 for 60,000 guilders early in 1884. Prager Tagblatt reported that the restaurant operated from 19 January that year. Police records reveal that Brejška moved here in 1884, was married and had children. He was also a dedicated sportsman, above all in cycling, and readily took on duties. He edited the guest house owner's magazine Hostimil and hosted their editorial offices at U Brejšky. Karel Brejška was a popular figure and when he died after long illness in 1923, Eduard Bass, a friend of Jaroslav Hašek, wrote a long obituary in Lidové noviny[a]. They were not the only newspaper that fondly remembered him. Brejška sold the restaurant three years before he died.

Modern times

In 1939 was still listed in the address book but whether or not there has been continuous operation is not known. In any case it still exists in a modern variation (2016) with the name Haškova restaurace U Brejsků. It is decorated with photos from the era (many of them feature Hašek) and makes the most of its connection with him. Their web page say little about the historical lines. Instead it focuses on Hašek and the fact that the sports club Slavia was formed here on 31 May 1895. The current restaurant is located in the basement.

The good soldier Švejk in captivity

The pub is also mentioned in Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí. In the first chapter it is revealed that the court medics at c.k. zemský co trestní soud fetched breakfast here when they discussed Švejk's case and his striking eagerness to serve his emperor.[1]

Pak přinesli soudním lékařům od Brejšky snídani a lékaři při smažených kotletách se usnesli, že v případě Švejkově jde opravdu o těžký případ vleklé poruchy mysli.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.2] Výjimku dělal neobyčejně tlustý pán s brýlemi, s uplakanýma očima, který byl zatčen doma ve svém bytě, poněvadž dva dny před atentátem v Sarajevu platil „U Brejšky“ za dva srbské studenty, techniky, útratu a detektivem Brixim byl spatřen v jejich společnosti opilý v „Montmartru“ v Řetězové ulici, kde, jak již v protokole potvrdil svým podpisem, též za ně platil.

Sources: Ladislav Hájek, Egon Erwin Kisch

Also written:Die ZecheReiner

Literature

- Jak jsem přemohl černošského obra Zippse ze Severní AmerikyJaroslav Hašek3.5.1912

- Soupis pražských domovských příslušníků 1830-1910 (1920)

- Mitteilungen aus dem Publikum19.1.1884

- Směna držebnosti16.2.1884

- Brejškův hostinec v Praze15.5.1884

- Brejškova restaurace1886

- .. vyš. hpospodárské ústav ..

- Brejška okraden26.7.1913

- Následek sporu typografů se zaměstnavateli6.2.1914

- Hádanka22.10.1914

- Restaurateur Brejška gestorben17.5.1923

- Karel Brejška zemřel17.5.1923

- Die Börse der Nachrichten6.12.1925

- Z historie

- Románové restaurační a jiné zábavní podniky2009 - 2021

| a | Otec Brejška mrtev | 17.5.1923 | |

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

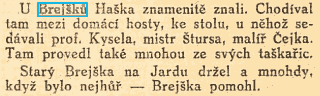

| Montmartre |  | ||||

| Praha I./224, Řetězová ul. 7 | ||||||

| ||||||

,2.9.1911

Montmartre is mentioned because the paper-shop owner who was Švejk's cell companion at c.k. policejní ředitelství had been observed drunk here together with the two Serbian students he had paid for earlier in the day, at U Brejšky.

Background

Montmartre was a café in the very centre of Prague which recently (as of 2010) was re-opened after a break of 70 years. The name is obviously taken from the famous Paris district of Montmartre. The café is decorated with period photos where Jaroslav Hašek plays a prominent role. The 1989 Sametová revoluce put a stop to official plans to turn Montmartre into a museum dedicated to Jaroslav Hašek.

Montmartre was opened in 1911 by the well-known actor and artist Josef Waltner. It was a night café and entertainment establishment, also known as Cabaret Montmartre. From the beginning it became a popular meeting place amongst artists, intellectuals and the bohemian set. Apart from Jaroslav Hašek it was also frequented by the likes of Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj, Max Brod, Egon Erwin Kisch, Franz Werfel and Franz Kafka. Hašek wrote four short stories where was Montmartre involved, and Kisch also immortalised the café through his writing[a].

Egon Erwin Kisch

Und einer von ihnen hatte doch während jener Tagung noch die Habsburger geschützt, indem er dem Delegierten Jaroslav Hašek auf dessen Zwischenruf: "Borg mir eine Krone" ex praesidio die feierliche Rüge ersteilte: "Bitte die Krone nicht in die Debatte zu ziehen".

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.2] Výjimku dělal neobyčejně tlustý pán s brýlemi, s uplakanýma očima, který byl zatčen doma ve svém bytě, poněvadž dva dny před atentátem v Sarajevu platil „U Brejšky“ za dva srbské studenty, techniky, útratu a detektivem Brixim byl spatřen v jejich společnosti opilý v „Montmartru“ v Řetězové ulici, kde, jak již v protokole potvrdil svým podpisem, též za ně platil.

Sources: Egon Erwin Kisch

Literature

- Románové restaurační a jiné zábavní podniky2009 - 2021

- Montmartre22.10.2023

- Černohorský jonák v úzkýchJaroslav Hašek1.8.1912

- Sen Josefa Waltnera, odvážného majitele kavárny MontmartreJaroslav Hašek1915

- Můj zlatý dědečekJar. Hašek1912

- Má tragedie montmartskáJaroslav Hašek1914

- Der Letzte vom Prager MontmartreMaxm. Huppert14.8.1928

| a | Zitate vom Montmartre |

| Spolek Dobromil |  | ||||

| Podolí/55, Kublov | ||||||

| ||||||

Garden restaurant in Hodkovičky, a possible location for Dobromil's celebration.

Address book from 1910

Spolek Dobromil was a charity in Hodkovičky who held a celebration on the day of the murders in Sarajevo. The police arrived and asked them to stop, but the chairman retorted that hey had to finish playing "Hej, Slované" (well known pan-slavic hymn) first. This led him straight to the cell at c.k. policejní ředitelství.

Background

Spolek Dobromil is an association which so far has not been fully identified. It is still very likely that they existed and may well have congregated in the centre of Hodkovičky. In 1910 such a society existed in nearby Podolí and Dvorce, so it is quite likely that these are the people Jaroslav Hašek refers to.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.2] Třetí spiklenec byl předseda dobročinného spolku „Dobromil“ v Hodkovičkách. V den, kdy byl spáchán atentát, pořádal „Dobromil“ zahradní slavnost spojenou s koncertem. Četnický strážmistr přišel, aby požádal účastníky, by se rozešli, že má Rakousko smutek, načež předseda „Dobromilu“ řekl dobrácky: „Počkají chvilku, než dohrajou ,Hej, Slované’.“

Sources: Milan Hodík

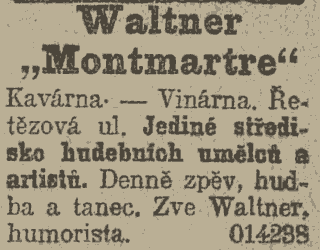

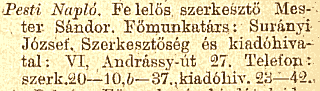

| Národní politika |  | ||||

| Praha II./835, Václavské nám. 21 | ||||||

| ||||||

,29.6.1914

,15.11.1915

Národní politika is first mentioned during the interrogation at c.k. policejní ředitelství when Švejk reveals that he reads the afternoon issue to look for dog adverts. He also uses the term "čubička" (the little bitch), which provokes the interrogator with the animal traits to shout: Out!.

Národní politika is mentioned again both in [I.6], [I.13] and in [II.2].

Background

Národní politika was a conservative daily that was published in Prague from 1883 to 1945. The editorial offices were located at Václavské náměstí. The paper printed at least six of Jaroslav Hašek's stories and it was one of the first papers to report both his capture in 1915 and his return to Prague (1920). In other stories he makes fun of the newspaper.

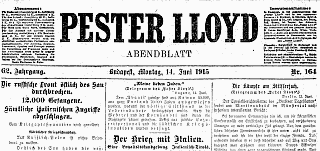

According to Franta Sauer it was the author's preferred newspaper, and at first sight it appears that he inserted snippets from it into The Good Soldier Švejk. The conversation between Oberleutnant Lukáš and hop trader Wendler in [I.14] reveals word for word quotes from the paper and the evening issue from 4 April 1915 is a prime example. That said, Kronika světové války is an even more obvious source for these fragments.

The good soldier Švejk in captivity

In Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí is actually Národní politika the first institution that is mentioned. Here and in other official publications an arrest order from c.k. zemský co trestní soud regarding Švejk was printed.[1]

Tak daleko jsi to tedy dopracoval, můj dobrý vojáku Švejku! V Národní politice a jiných úředních věstnících objevilo se tvé jméno spojené s několika paragrafy trestního zákona.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.2] „S kýmpak se stýkáte?“ „Se svou posluhovačko, vašnosti.“ „A v místních politických kruzích nemáte nikoho známého?“ „To mám, vašnosti, kupuji si odpoledníčka „Národní politiky“, ,čubičky’.“ „Ven!“ zařval na Švejka pán se zvířecím vzezřením.

[I.6] posledně od toho pana řídícího z Brna ta záloha šedesát korun na angorskou kočku, kterou jste inseroval v Národní politice a místo toho jste mu poslal v bedničce od datlí to slepé štěňátko foxteriéra.

[I.13] Když tenkrát ta sopka Mont Pelé zničila celý ostrov Martinique, jeden profesor psal v Národní politice, že už dávno upozorňoval čtenáře na velkou skvrnu na slunci. A vona, ta Národní politika, včas nedošla na ten vostrov, a tak si to tam, na tom vostrově, vodskákali."

[II.2] I u nás jsou nadšenci. Četli v ,Národní politice’ o tom obrlajtnantovi Bergrovi od dělostřelectva, který si vylezl na vysokou jedli a zřídil si tam na větví beobachtungspunkt?

Also written:National PoliticsenNationalpolitikdeNasjonal Politikkno

Literature

- Vánoce Národní politikyJaroslav Hašek29.12.1907

- Písemnictví4.4.1915

- Malý oznamovatel Národní politikyJaroslav Hašek8.2.1921

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

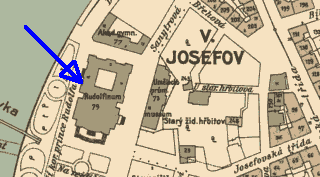

| Museum |  | |||

| Praha II./1700, Václavské nám. 74 | |||||

| |||||

Světem letem, ,1896

Museum is mentioned in an anecdote by Švejk about quartering av prisoners in the bad old days. This is supposed to have happened on a hill somewhere by the museum. The museum itself is later mentioned explicitly in an anecdote on the way to Budapest.

Background

Museum which is talked about is certainly the main building of Museum království Českého, now Národní muzeum in Prague. It is located at the southern end of Václavské náměstí. The building was erected between 1885 and 1891.

The good soldier Švejk in captivity

Museum is mentioned also in Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí when is pushed to the draft board in a wheelchair.[1]

Lidé se smáli, přidávali se k zástupu a u Muzea dostal nějaký žid, který zvolal "Heil!", první ránu.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.2] Takovejch případů bylo víc a ještě potom člověka čtvrtili nebo narazili na kůl někde u Musea

Literature

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

|

I. In the rear |

| |

3. Švejk before the court physicians | |||

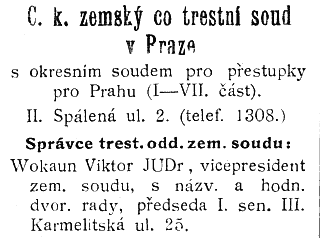

| C.k. zemský co trestní soud |  | |||||

| Praha II./6, Spalená 2 | |||||||

| |||||||

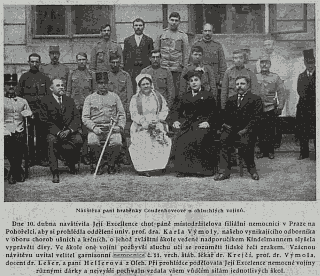

Kol. 1920 (?) Celkový pohled na dům čp. 6 (trestní soud) na nároží Karlova náměstí a Spálené ulice (vlevo) na Novém Městě.

Doctors at the prison

,1907

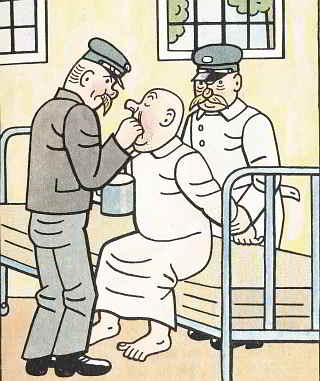

C.k. zemský co trestní soud is the institution Švejk was driven to in a police car the morning after the arrest. Here he was interrogated by a good-natured judge who, when he read what Švejk had confessed to, questioned his mental health. He concluded that Švejk had to undergo an investigation by a psychiatric commission, which resulted in him being sent to a lunatic asylum.

Background

C.k. zemský co trestní soud was the criminal court for Prague, a department of C. k. zemský soud (k. k. Landesgericht), the highest judicial instance in the Kingdom of Bohemia. It was located in the enormous judiciary complex between Spálená ulice, Karlovo náměstí and Vodičkova ulice. The court also contained a prison. Today this building houses the City Court of Prague.

Hašek before the court

The author of The Good Soldier Švejk was taken to court here after he at an anarchist meeting on 1 May 1907 allegedly incited violence against the police. For this he was sentenced to a month in prison, his longest conviction ever. The verdict fell on 1 July[b] and he served the prison term from 16 August to 16 September.

In 1906 the criminal court employed three medical doctors[c] and it is quite likely that Hašek was in contact with at least one of them during his month in prison.

The good soldier Švejk in captivity

The country court as criminal court features also in Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí. Švejk's eagerness to serve his emperor is so striking that the authorities perceived it as subversion and took him to court.[1]

"C. k. zemský jakožto trestní soud v Praze, oddělení IV, nařídil zabaviti jmění Josefa Švejka, obuvníka, posledně bytem na Král. Vinohradech, pro zločin zběhnutí k nepříteli, velezrády a zločin proti válečné moci státu podle § 183-194, č. 1334, lit. c, a § 327 vojenského trestního zákona."

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] Čisté, útulné pokojíky zemského „co trestního soudu“ učinily na Švejka nejpříznivější dojem. Vybílené stěny, černě natřené mříže i tlustý pan Demartini, vrchní dozorce ve vyšetřovací vazbě s fialovými výložky i obrubou na erární čepici. fialová barva je předepsána nejen zde, nýbrž i při náboženských obřadech na Popeleční středu i Veliký pátek.

Also written:Country- as Criminal CourtenLandes- als StrafgerichtdeLandsretten som strafferettno

| b | Ze soudní sine | 2.7.1907 | |

| c | Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních | 1907 | |

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

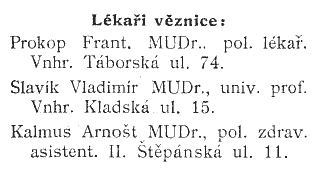

| Teissig |  | |||||

| Praha II./85, Spálená ul. 5 | |||||||

| |||||||

Teissigova plzeňská restaurace,1915

© Photogen.cz

,1.1.1896

Teissig was a restaurant where the employees of c.k. zemský co trestní soud went to fetch peppers and Pilsner beer for lunch. Why they went to get peppers is a mystery. Translators Grete Reiner and Cecil Parrott both interpreted it as goulash, probably a bit far-fetched.

Hans-Peter Laqueur has voiced the theory that the author by "paprika" meant "paprikash" which is the Hungarian goulash, a soup that is quite different from Czech "guláš". In that case, Reiner and Parrott's interpretation is more accurate than "peppers".

Background

Teissig was a restaurant located across the street from the massive City Court complex (former c.k. zemský co trestní soud) and owned by Karel Teissig. He had been running the restaurant at least since 1895. Teissig had previously managed U kotvy, two houses down the road. This restaurant that still exists (2019). Address books confirm that U Teissigů was operating as late as 1940.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] A vyšetřující soudcové, Piláti nové doby, místo aby si čestně myli ruce, posílali si pro papriku a plzeňské pivo k Teissigovi a odevzdávali nové a nové žaloby na státní návladnictví.

Literature

- Románové restaurační a jiné zábavní podniky2009 - 2021

- Anzeige3.6.1896

- Besitzwechsel3.6.1899

- Českoslovanská záložna v Praze-II.25.2.1910

| Státní návladnictví |  | ||||

| Praha III./2, Malostranské nám. 25 | ||||||

| ||||||

Státní návladnictví was where the detainees were led after their stay at c.k. zemský co trestní soud. Here formal prosecution was in store. The institution had also been briefly mentioned in [I.1].

Background

Státní návladnictví is a term that is rarely used in modern Czech, and is now mostly referred to as Státní zastupitelství, a wording that was used even during the life-time of the author (see cut from the 1907 address book). The expression refers to the state prosecutor's office. Their main seat for Bohemia was at Malostranské náměstí in the building of the regional high court, and their Prague office was located in the same building as c.k. zemský co trestní soud. It is surely those premises that the author had in mind.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] A vyšetřující soudcové, Piláti nové doby, místo aby si čestně myli ruce, posílali si pro papriku a plzeňské pivo k Teissigovi a odevzdávali nové a nové žaloby na státní návladnictví.

Also written:State prosecutor's officeenStaatsanwaltschaftdeStatsadvokatkontoretno

| U Bansethů |  | |||||

| Nusle/389, Palackého tř. 18 | |||||||

| |||||||

U Bansethů, 2011

,27.2.1906

,1.9.1907

,21.3.1908

U Bansethů crops up in one of Švejk's stories. He was on his way back from this pub when he was assaulted by the bridge across Botič. The perpetrators got the wrong man and gave him an extra slap due to the disappointment.

The tavern is mentioned again in [I.13] in the discussion about volcanic eruptions and sunspots. See Martinique.

It also appears in the final chapter of the novel, and now the owner Banseth is mentioned directly.

Background

U Bansethů was the name of two restaurants in Nusle, owned by Alois Banseth. One of them is still operating and it advertises its connection to Švejk; the interior has numerous pictures of Jaroslav Hašek. There is even a Stůl Jaroslava Haška (Jaroslav Hašek's table).

The original restaurant was located a few steps down the street in house No. 321. Banseth started operation in the autumn of 1900 and in March 1908 it was announced that it was sold to František Kocan, former landlord at U Kocanů. Around the same time he bought house No. 389 which still bears his name. The pub already existed under the name U Palackého and Banseth with his wife Anna paid 100,000 crowns for the house.

Which of the two public houses the author had in mind is uncertain, but the address information given above relates to the one that still exists. Mr. Banseth was in 1910 listed as owner of the building that housed his pub. He also lived here.

The original U Bansethů also arranged public meetings on its premises, for instance on 26 February 1906 where anarchists took part, and amongst them Jaroslav Hašek was very likely to be found. On this occasion the anarchist Čeněk Körber (1875-1951) caused such uproar that the meeting was abandoned. The pub was also hosted meetings by Česká strana národně sociální, Sokol, Volná myšlenka and Mladočeši. Particularly the first seemed to have met a lot here, and in Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona Jaroslav Hašek describes on of their meetings where he provoked and caused disorder.

Strana mírného pokroku

Po onom velkém morálním vítězství U Banzetů sešly se naše rozptýlené řady až nahoře na Havlíčkově třídě. Kulhal jsem, pod okem jsem měl modřinu a mé tváře, jak praví Goethe, nevěstily nic dobrého. Byly opuchlé!

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] Jako jednou v Nuslích, právě u mostu přes Botič, přišel ke mně v noci jeden pán, když jsem se vracel od Banzetů, a praštil mě bejkovcem přes hlavu, a když jsem ležel na zemi, posvítil si na mne a povídá: ,Tohle je mejlka, to není von.’

[I.13] „Ty skvrny na slunci mají vopravdu velkej význam,“ zamíchal se Švejk, „jednou se vobjevila taková skvrna a ještě ten samej den byl jsem bit ,U Banzetů’ v Nuslích.

[IV.3] Vona potom chtěla mít celou soupravu do domácnosti z takovejch nožů a posílala ho vždycky v neděli do Kundratic na vejlet, ale von byl tak skromnej, že nešel nikam než k Banzetovům do Nuslí, kde věděl, že když sedí v kuchyni, že ho dřív Banzet vyhodí, než může na něho někdo sáhnout.“

Sources: Jaroslav Šerák

Also written:U BanzetůHašek

Literature

- Románové restaurační a jiné zábavní podniky2009 - 2021

- Strana roste, ale je bita

- V zajetí Kartagiňanú

- Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství1851 - 1914

- Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních (1910)

- Besitzwechsel10.7.1900

- Hostinský věstník2.11.1900

- Zábavy2.5.1901

- Rozpuštěná schůze27.2.1906

- Změny držebnosti21.3.1908

- K jubileu "Národních Listů"21.12.1929

| Podolský kostelík |  | ||||

| Podolí/91, Přemyšlova ul. - | ||||||

| ||||||

Adresář Prahy (1907)

Podolský kostelík is mentioned in the series of stories about various mistakes that Švejk tells his fellow remand prisoners at c.k. zemský co trestní soud. A lathe operator (turner) who lived in Švejk's house locked himself into the chapel by mistake once he was drunk, and because he thought he was at home he slept overnight and the result was that the church had to be re-consecrated. The unfortunate intruder was convicted and died at Věznice Pankrác.

Background

Podolský kostelík is almost certainly the parish church kostel sv. Michala (Church of Saint Michael) in Podolí, south of Vyšehrad.

Jaroslav Šerák

Podolský kostel bude určitě kostel svatého Michala v ulici Pod Vyšehradem, je to farní kostel dodnes. Ostatní jsou jen hřbitovní kaple, nebo postavené později.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] Nebo vám povím příklad, jak se zmejlil u nás v domě jeden soustružník. Votevřel si klíčem podolskej kostelík, poněvadž myslel, že je doma, zul se v sakristii, poněvadž myslel, že je to u nich ta kuchyně, a lehl si na voltář, poněvadž myslel, že je doma v posteli, a dal na sebe nějaký ty dečky se svatými nápisy a pod hlavu evangelium a ještě jiný svěcený knihy, aby měl vysoko pod hlavou.

Sources: Jaroslav Šerák

Literature

| Česká radikální strana |  | |||

| |||||

Karel Baxa, member of parliament from 1903-1918 and chairman of Státoprávně radikální strana

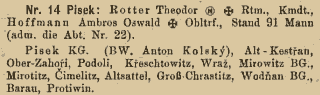

Česká radikální strana is indirectly referred to in Švejk's story about the Czech radical deputy who by mistake is chased by Rittmeister Rotter's police dogs.

Background

Česká radikální strana was not the name of any particular political party but it is quite obvious that Švejk had either Strana radikálně pokroková or Státoprávně radikální strana in mind. The former party existed from 1897 to 1908 and campaigned for extensive political reforms, whereas the latter was formed in 1899 and their main goal was extended state rights for the Czech lands.

In 1908 he two parties merged and founded Česká strana státoprávně pokroková. From 1914 the party openly campaigned for an independent Czech state and suffered persecution as a result. It can not be ruled out that label "radical" stuck with even the new party and that indeed was them Švejk had in mind.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] Nakonec se ukázalo, že ten člověk byl českej radikální poslanec, kterej si vyjel na vejlet do lánskejch lesů, když už ho parlament vomrzel.

Literature

| Parlament |  | |||

| Wien I., Franzens-Ring 1 | |||||

| |||||

Abgeordnetenhaus 1907

A selection of Czech deputies in Reichsrat in 1914 (Josef Švejk highlighted).

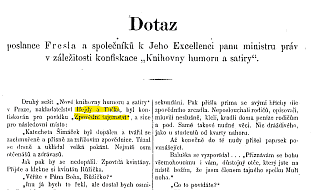

Interpellation regarding the confiscation of Hašek's book.

, 29.11.1911

Parlament is mentioned is Švejk's story about the Czech radical member of parliament who by mistake is chased by Rittmeister Rotter's police dogs.

In [II.2] it is mentioned again because of Major Wenzl's outrageous behaviour in Kutná Hora was reported by some deputy.

Background

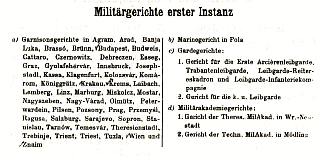

Parlament refers to Reichsrat in Vienna. From 1867 until 1918 it was the national assembly of Cisleithania, i.e. the Austrian part of the Dual Monarchy. The council consisted of a Herrenhaus (House of Lords) and a Abgeordnetenhaus (House of Commons).

The last election to the Abgeordnetenhaus was held in June 1911, and that year the house counted 516 deputies, of which 232 were Germans, 108 Czechs and 83 Poles. The remaining seats were occupied by Ukrainians, Slovenes, Italians, Romanians, Croats, Serbs and a lone Zionist!

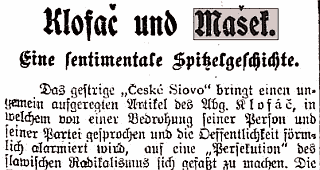

Several of the politicians mentioned in The Good Soldier Švejk were deputies at the outbreak of war: Professor Masaryk, Kramář, Klofáč, Jos. M. Kadlčák, and a certain agrarian politician Josef Švejk. A former deputy of interest for readers of The Good Soldier Švejk was Alexander Dworski, see Mr. Grabowski. The parliament was suspended at the outbreak of war in 1914 and was only reconvened in 1917.

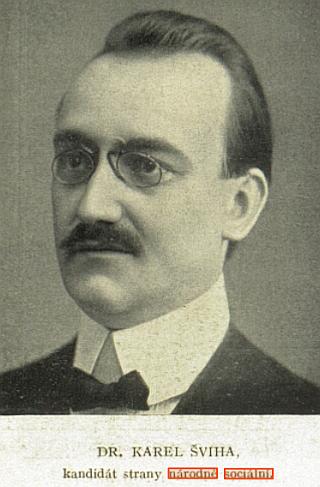

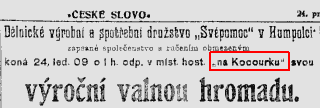

Hašek's story in Reichsrat

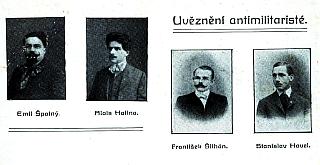

On 29 November 1911 one of Jaroslav Hašek's stories was the subject of an interpellation in the deputy chamber of Reichsrat[a]. It was one of several tales in Hašek's Dobrý voják Švejk a jiné podivné historky, a book that was published in the autumn of 1911. The k.k. Landesgericht als Preßgericht in Prague on 18 November 1911 decided to confiscate the book because of the story Zpovědní tajemství (The seal of confession)[b] because it was deemed blasphemous. A group of deputies with Fresl at the front protested to the minister of justice. They pointed at that the story had been printed in České slovo already in 1908 without having been censored.

The 18 signatories were: eleven from Česká strana národně sociální (Fresl, Vojna, Formánek, Klofáč, Choc, Stříbrný, Lisy, Konečný, Slavíček, Baxa, Šviha), three Czech independent progressives (Professor Masaryk, Kalina, Prunar), two Czech agrarians (Masata, Bradač) and even two Ukrainians (Breiter, Трильовський (Trylowskyj)). Note that the agrarian Josef Švejk didn't sign it... The complaint seems to have been heeded because in 1912 the book was printed again. The segments that had been censored were marked with a note about the petition but nothing seems to have been removed. The interpellation didn't mentioned Hašek or the book's title by name.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] Nakonec se ukázalo, že ten člověk byl českej radikální poslanec, kterej si vyjel na vejlet do lánskejch lesů, když už ho parlament vomrzel. Proto říkám, že jsou lidi chybující, že se mejlejí, ať je učenej, nebo pitomej, nevzdělanej blbec. Mejlejí se i ministři.“

[I.8] Voba byli svázaní do kozelce a regimentsarzt je kopal do břicha, že jsou prej simulanti. Pak když ty voba vojáci umřeli, přišlo to do parlamentu a bylo to v novinách.

[II.2] Slovo padlo, a už to bylo v místních novinách a nějaký poslanec interpeloval chování hejtmana Wenzla v hotelu ve vídeňském parlamentě.

Literature

- Stenographische Protokolle des Abgeordnetenhauses des Reichsrates 1861-1918

- Parlament

- Reichsrat

- Parlaments-Gebäude

| a | Stenographische Protokolle - Abgeordnetenhaus | 29.11.1911 | |

| b | Kundmachungen | 23.11.1911 |

|

I. In the rear |

| |

4. They threw Švejk out of the madhouse | |||

| Blázinec |  | |||||

| Praha II./468, Ul. Karlova 15 | |||||||

| |||||||

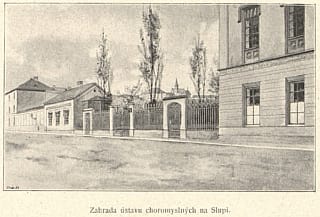

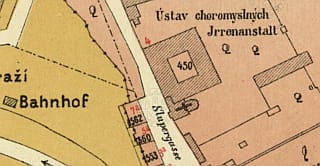

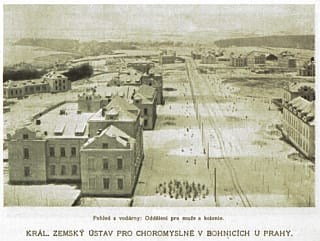

Blázinec is referred to when Švejk is led to a psychiatric institution after a commission of psychiatrists conclude that he is a "malingerer with a feeble mind". He might have spent several weeks here as he was only released on 29 July 1914, the day Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia.

Background

Blázinec was some mental hospital in Prague which is not explicitly located. Still, we can by near certainty conclude that the author had Kateřinky in mind. This is an institution where he himself spent a few weeks in February 1911.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.4] Když později Švejk líčil život v blázinci, činil tak způsobem neobyčejného chvalořečení: „Vopravdu nevím, proč se ti blázni zlobějí, když je tam drží. Člověk tam může lézt nahej po podlaze, vejt jako šakal, zuřit a kousat. Jestli by to člověk udělal někde na promenádě, tak by se lidi divili, ale tam to patří k něčemu prachvobyčejnýmu. Je tam taková svoboda, vo kterej se ani socialistům nikdy nezdálo.

Also written:The madhouseenDas IrrenhausdeGalehusetno

| Ottův slovník naučný |  | ||||

| Praha II./553, Karlovo nám. 35 | ||||||

| ||||||

Ottův slovník naučný, , 1892

,1910-1914

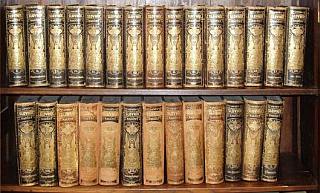

Ottův slovník naučný was mentioned in connection with the patient at blázinec who claimed to be the 16th volume of this encyclopedia.

Background

Ottův slovník naučný is an encyclopaedia by the publisher Otto that is regarded an outstanding work of reference also in an international context. A total of 28 volumes were released between 1888 and 1909 with additional supplements appearing thereafter. Otto's Encyclopaedia was at the time one of the largest in the world. The editorial offices were at Karlovo náměstí, in the building next to the publishing house of Otto.

Emil Artur Longen (1928) claims that Jaroslav Hašek made active use of the encyclopaedia when he wrote The Good Soldier Švejk. He may well have a point as the long tirade Rekrut Pech used is almost a direct quote from the encyclopaedia.

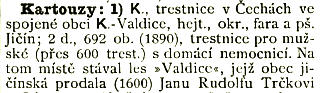

The reference to kartonážní šička (cardboard stapler) can not be found in volume 16 (Lih-Media) and Antonín Měšťan also points out that there is no such entry in the encyclopaedia at all. If it had been a real entry it would have been found in volume 14. This volume does however have a reference to kartonáž that simply points to the entry cartonage in volume 5.

Antonín Měšťan

Durch einen Blick in den Ottův slovník naučný läßt sich leicht feststellen, daß das Stichwort "Kartonagenähgrin" nicht nur im 16. Band fehlt - es fehlt in diesem Lexikon überhaupt.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.4] Nejzuřivější byl jeden pán, kerej se vydával za 16. díl Ottova slovníku naučného a každého prosil, aby ho otevřel a našel heslo ,Kartonážní šička’, jinak že je ztracenej.

Sources: Antonín Měšťan, Emil Artur Longen

Also written:Otto's encyclopaediaenOttos KonversationslexicondeOttos konversasjonsleksikonno

Literature

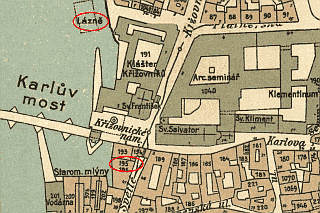

| Královy lázně |  | |||

| Praha I./195, Ul. Karoliny Světlé 43 | |||||

| |||||

, 1910-1914

Břetislav Hůla

Baedeker

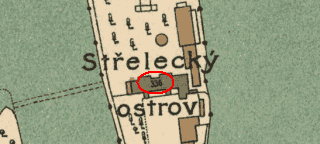

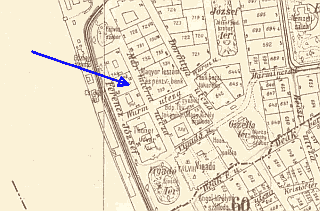

Královy lázně is indirectly mentioned by Švejk when he in blázinec is asked if he enjoys likes getting a bath. "It is better than at the baths by Charles Bridge", is the answer.

Background

Královy lázně was a public bath at the end of Karlův most and is listed on the address Karoliny Světlé 43, indicated on the map. This is confirmed by Baedeker Österreich 1913 that refers to them as Königsbad.

Some baths north of the bridge are also shown, called Gemeindebad (Municipal Bath). This was more likely an open-air bath and to judge by the description in the novel, Švejk is almost certainly talking about the more luxurious indoor Royal Baths.

Břetislav Hůla refers to the bath as Karlovy lázně (Charles' Bath) and this corresponds to the entry in the address book of 1936. It is not known when exactly the renaming took place.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.4] V koupelně ho potopili do vany s teplou vodou a pak ho vytáhli a postavili pod studenou sprchu. To s ním opakovali třikrát a pak se ho optali, jak se mu to líbí. Švejk řekl, že je to lepší než v těch lázních u Karlova mostu a že se velmi rád koupe.

Sources: Archiv Hlavního Města Prahy (Sbírka map a plánů)

Also written:Royal BathenKönigsbadde

Literature

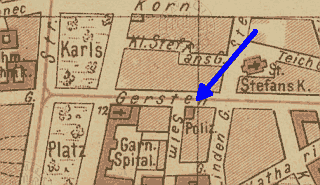

| Regimentskanzlei Budweis |  | ||||

| Karlín/20, Palackého třída 10 | ||||||

| ||||||

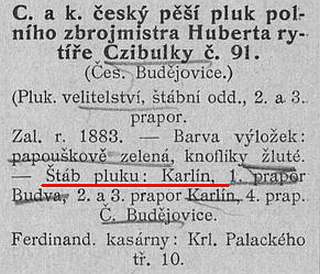

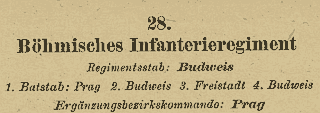

Regimentskanzlei Budweis is mentioned by Švejk when he tells the medical commission at blázinec that he has been released from the army due to feeblemindedness. He adds that this can be confirmed at the Ergänzungskommando in Karlín or the regimental office in Budějovice.

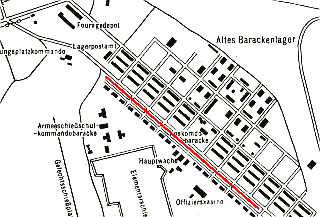

Background

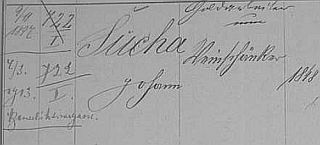

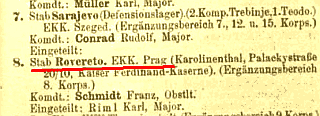

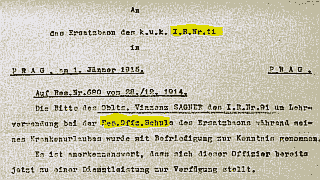

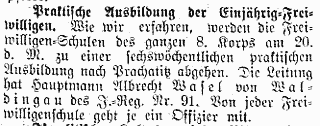

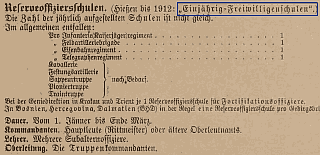

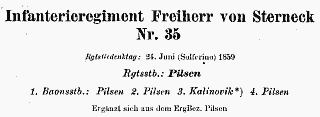

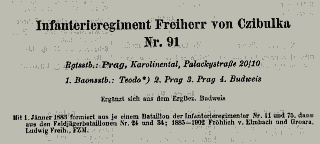

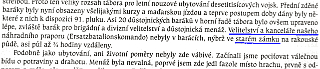

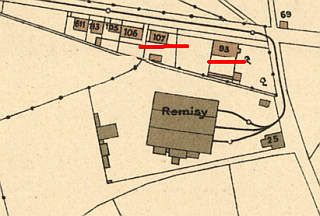

Regimentskanzlei Budweis (main regimental staff office) was in 1914 stationed in Karlín and not in Budějovice as Švejk claims. When the war started, several regimental functions were indeed located in Ferdinandova kasárna in Karlín: 2. field battalion, regimental staff and IR. 91 regimental command itself. This inconsistency is probably due to a mix-up with the Ergänzungsbezirkskommando which together with the 4th battalion and Ersatzbataillon IR. 91 were indeed stationed in Budějovice.

We should also take into account that the barracks in Karlín were converted to a Red Cross reserve hospital soon after the outbreak of war and that the administrative functions of the regiment would now have been moved, some of them no doubt to Budějovice, and others to the front. See Ergänzungskommando.

The good soldier Švejk in captivity

In Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí the regiment's office and the barracks where it was located the starting point of the plot. Švejk resisted attempt to dismiss him from the army, he wanted to serve his emperor. It is also informed that the barracks were built by emperor Josef II.[1]

V kanceláři regimentu pod číslem 16112 byl uschován akt týkající se průběhu i výsledku superarbitračního řízení s dobrým vojákem Švejkem.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.4] „Já, pánové,“ hájil se Švejk, „nejsem žádný simulant, já jsem opravdovej blbec, můžete se zpravit v kanceláři jednadevadesátýho pluku v Českých Budějovicích nebo na doplňovacím velitelství v Karlíně.“

Also written:Regimental officeenPlukové kancelářczRegimentskontoretno

Literature

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| Ergänzungskommando |  | ||||

| Budějovice, Pekárenská ulice | ||||||

| ||||||

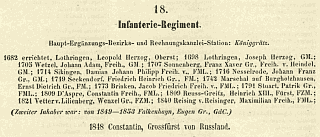

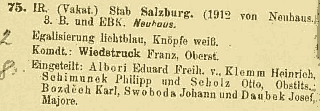

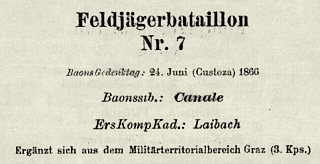

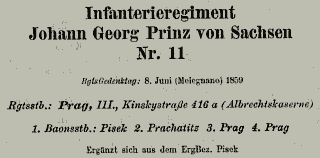

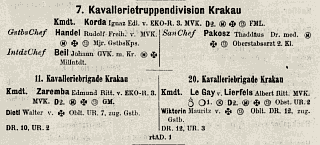

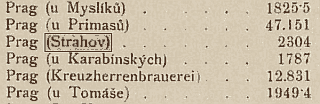

IR91, Seidels kleines Armeeschema August 1914

91. Ergänzungsbezirk

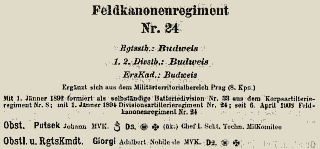

Ergänzungskommando is mentioned by Švejk when he tells the medical commission at blázinec that he has been released from the army due to feeble-mindedness. He adds that this can be confirmed at the reserve command in Karlín or Regimentskanzlei Budweis in Budějovice.

Background

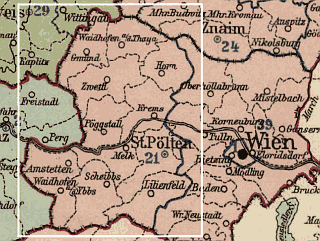

Ergänzungskommando by near certainty refers to Ergänzungsbezirkskommando Budweis. It was located in Backhaus in Budějovice (Pekárenská ulice) and not in Karlín as Švejk tells the doctors. At the outbreak of war, several other regimental functions resided Ferdinandova kasárna in Karlín: III. Feldbataillon, regimental staff and IR. 91 Regimentskommando itself. We may therefore be witnessing a straight mix-up between Regimentskanzlei Budweis and Ergänzungsbezirkskommando. Both are mentioned in the same sentence, so Švejk appears to have swapped the respective locations.

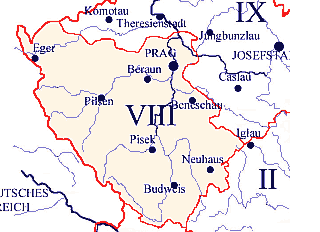

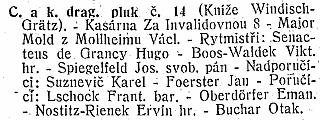

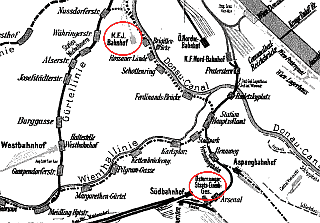

The district reserve command Budweis (until 1912 Nr. 91 Budweis) was resposible for draft and call-up of reserves in Ergänzungsbezirk Budweis, see map. The recruitment district covered five hejtmanství: Budějovice, Týn nad Vltavou, Kaplice, Krumlov and Prachatice. The army units that the district provided recruits for were IR. 91 and 14. Dragonerregiment.

Commander in 1914 was colonel Johann Splichal but he was sent to the front soon after hostilities began, and it is not clear who replaced him. Splichal was also head of Ersatzbataillon IR. 91, and in this role, he was replaced by Karl Schlager. It may also be that the latter also succeeded him as head of the district reserve command. Usually, these two positions were held by the same officer. That would however not have been the case after 1 June 1915 when the replacement battalion was transferred to Királyhida, whereas the recruitment command for obvious reasons remained in its home district.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.4] „Já, pánové,“ hájil se Švejk, „nejsem žádný simulant, já jsem opravdovej blbec, můžete se zpravit v kanceláři jednadevadesátýho pluku v Českých Budějovicích nebo na doplňovacím velitelství v Karlíně.“

[II.2] Že jsem mohl být felddienstunfähig. Taková ohromná protekce! Mohl jsem se válet někde v kanceláři na doplňovacím velitelství, ale má neopatrnost mně podrazila nohy.“

Also written:Replenishment commandenDoplňovací velitelstvíczRekrutteringskommandono

Literature

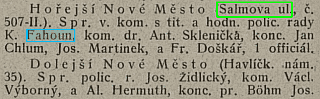

| Policejní komisařství Salmova ulice |  | |||||

| Praha II./507, Salmovská ul. 20 | |||||||

| |||||||

Politický kalendář, 1910

, 1910

Zum Wortschatz des tschechischen Rotwelsch, , 1926

Ve dvou se to lépe táhne, , Z.M. Kuděj

Denní raport - c.k. okresního policejního komisařství III.z. 31./12. 1908

Československá republika, 26.6.1926

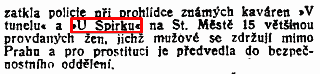

Policejní komisařství Salmova ulice is the scene of a full chapter in the novel. Švejk is taken straight here after refusing the leave blázinec without lunch. His first encounter is with the brutal police inspector Inspektor Braun but then the plot revolves mostly around a conversation with his fellow inmate, a very solid citizen who for the moment has slid off the path of virtue. Švejk does his utmost to convince him that his situation is hopeless.

The stay here was only one afternoon, and Švejk taken to the first floor for interrogation, this time by a fat and friendly police officer. Under escort he is led from the guard house (see Strážnice) on the ground floor onwards to c.k. policejní ředitelství. It was on the way he read the emperor's declaration of war.

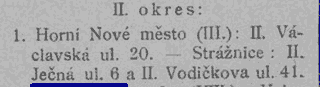

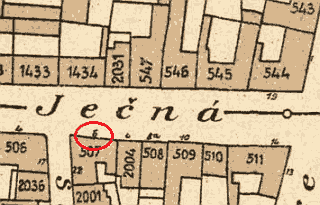

Background

Policejní komisařství Salmova ulice was the police station of the 3rd police district (Hořejší Nové Město - Upper New Town) in Prague, called "Salmovka" in common speech. It was located on the corner of Ječná ulice and Salmovská ulice. The police station was operating until 29 June 1926 when it was moved to Krakovská ulice where it is still located. The building was subsequently demolished and in 1928 the current edifice was erected on the site.

The station was often called "Salmovka" in day-to-day speech, a term used by e.g. Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj in one of his books about Jaroslav Hašek (Ve dvou se to lépe táhne, 1924). The term is also listed in a German-language dictionary of Czech slang (Eugen Rippl, 1926).

Chief inspector in 1906 and until 1910 was Karel Fahoun, and he was succeeded by Antonín Sklenička. No evidence has been found, in address books or elsewhere, that any Inspektor Braun ever served here.

Hašek at Salmovská

This is a police station that Jaroslav Hašek knew well, because it within this police district he was born and grew up. Also in his adult life he for the most part lived within its jurisdiction. He was christened in Kostel sv. Štefána in the immediate vicinity and on several occasions he lived only a few steps away. It has also been claimed that the author was a personal friend of police chief Karel Fahoun and his family but Břetislav Hůla refutes this claim after consulting Fahoun's son.

Police records from 1902 to 1912 reveal that Jaroslav Hašek was brought to the station several times. Most of the cases refer to breaches of public order and small-scale vandalism, induced by drinking. On New Years eve 1908 he and the Croat student Rudolf Giunio were arrested and locked up here after a pub brawl. Hašek was handed five days in prison for his efforts. See Bendlovka for more information about this incident.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.5] Švejk prohlásil, že když někoho vyhazují s blázince, že ho nesmějí vyhodit bez oběda. Výtržnosti učinil konec vrátným přivolaný policejní strážník, který Švejka předvedl na policejní komisařství; do Salmovy ulice.

[I.5] „Víte co, Švejku,“ řekl vlídně pan komisař, „nač se zde, na Salmovce, máme s vámi zlobit? Nebude lepší, když vás pošleme na policejní ředitelství?“

Sources: Hůla, Sergey Soloukh, Jaroslav Šerák

Also written:District police station No. 3enPolizeikommisariat Nr. IIIdeBydelspolitistasjon Nr. 3no

Literature

|

I. In the rear |

| |

5. Švejk at the district police station in Salmova street | |||

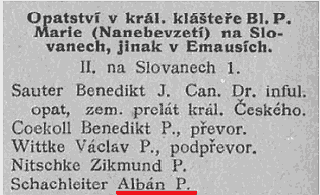

| Emauzský klášter |  | ||||

| Praha II./320, na Slovanech 1 | ||||||

| ||||||

The monastery at the turn of the century

Address book 1907

Emauzský klášter is the place where a monk is supposed to have hung himself in a crucifix according to Švejk. This is a story he tells his unfortunate cell-mate at Salmova ulice police station, when the latter wants to hang himself.

The monastery is mentioned again in [I.9] as the place where Feldkurat Katz was baptised. The priest who christened him was páter Albán, see páter Albán.

In [I.13] the monastery is mentioned for the third time, now by Švejk who tells Feldkurat Katz about a gardening assistant who worked there.

Background

Emauzský klášter is a Benedictine monastery in Prague, located south of Karlovo náměstí. It was founded by emperor Charles IV in 1347. The abovementioned páter Albán served as abbot here from 1908 until 1918 and during the war a part of the monastery was converted to a hospital for soldiers.

After the proclamation of Czechoslovak independence on 28 October 1918 the abbot and the German monks left the country after they were subjected to harassment from crowds and militia groups. This was caused by accusations in the press, one of them being that they spied for Germany.

The monastery was badly damaged during an allied bomb raid in 1945, and was reconstructed in a somewhat different style after the war. It was confiscated by both the Nazis (1941) and the communists (1950) but was in 1990 returned to the Benedictine order.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.5] Ledaže byste se pověsil vkleče u pryčny, jako to udělal ten mnich v klášteře v Emauzích, co se oběsil na krucifixu kvůli jedný mladý židovce.

[I.9] Křtili ho slavnostně v Emauzích. Sám páter Albán ho na máčel do křtitelnice.

[I.13] "Tak si koupíme katechismus, pane feldkurát, tam to bude," řekl Švejk, "to je jako průvodčí cizinců pro duchovní pastýře. V Emauzích pracoval v klášteře jeden zahradnickej pomocník, ...

Also written:Emmaus MonasteryenEmmausklosterdeCloître d'EmmaüsfrEmmausklosteretno

Literature

- Pohled do vojenské nemocnice v pražském klášteře emauzském2.10.1914

- Historie Emauzského opatství

- Klášter EmauzyZdeňka Kuchyňová

| Bendlovka |  | |||||

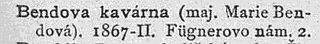

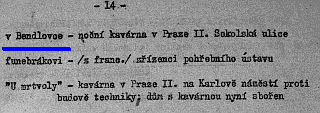

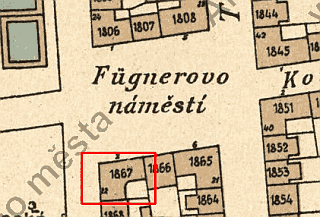

| Praha II./1867, Fügnerovo nám. 2 | |||||||

| |||||||

Břetislav Hůla, 1951

© AHMP

Denní raport - c.k. okresního policejního komisařství III.z. 31./12. 1908

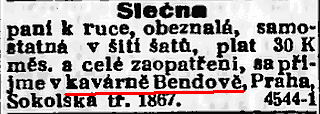

Bendlovka is mentioned in a story Švejk "comforts" his cell-mate at Policejní komisařství Salmova ulice with. Švejk had once at Bendlovka slapped an undertaker, who had returned the compliment. The next day it was in the newspapers.

Background